What was in it for them, for Steven Farag, the CEO of Campus Ink, who sank deeper into a leather couch with every Michigan score? Well, money, first and foremost. But it also would have been another step forward for a merchandise company that couldn’t have imagined this three years ago, before college athletes could profit off their name, image and likeness (NIL). Campus Ink, as it was, wouldn’t have had Washington as a client, or a chance to print thousands of championship tees to benefit the school’s athletes, or even the thought that one night could turn a down month into a windfall.

But that was Farag’s wish. To wake up the next morning, his phone buzzing nonstop, and find the right kind of chaos inside Campus Ink’s production facility in central Illinois. His company’s business hack is giving more money to athletes — more than Nike, Adidas, Under Armour or Fanatics — after selling a shirt, jersey or sweatshirt with the athlete’s name and number on it.

Campus Ink revenue-shares about 20 percent with athletes on each item sold online, whereas a more a standard industry rate is between 6 and 10 percent. In 2022, Fanatics and OneTeam Partners, a group licensing company, were giving football players less than 5 percent on jerseys that sold for about $140 (which ultimately netted less than $4 for the athlete on every sale). Campus Ink, by contrast, has an influencer model that averages to $6 to $8 for the athlete on every tee, $8 to $10 on every crew neck and $12 to $15 on every hoodie and jersey.

So while legacy brands may not love Campus Ink’s approach, plenty of athletes, schools and donor-funded collectives do. Campus Ink has license agreements with 42 Division I schools and has signed more than 8,600 athletes to sell their NIL merchandise. The license agreements allow the company to use each school’s logos on customized NIL gear. Beyond their cut through licensing fees, schools can then sell Campus Ink as another NIL perk for their athletes, whether they leverage that in recruiting or use it to help keep players happy and on campus. It all taps into the way of the new college sports world.

“Steven is a gambler,” said Jedd Swisher, who co-owns Campus Ink with the 32-year-old Farag. “In a way, he’s gambling with his livelihood with how hard it is to sustain and grow a small business in this crazy NIL world. But he’s given everyone here every reason to trust him.”

Their arc, just like the arc of college sports, is split clean between before and after July 1, 2021, when the NCAA permitted NIL deals and a whole industry formed overnight. A volatile market has since weeded out strivers by the hundreds. The pie is only so big, no matter how huge it might seem on social media or during the College Football Playoff. But Campus Ink is taking more and more of it.

That’s why the national championship game wasn’t make-or-break, even if it would have been nice to cash in. Campus Ink projects to have license agreements with around 100 schools by the end of the year, and it recently launched its online platform, NIL Store, with North Carolina and Georgetown. When Campus Ink adds a school, each athlete — from football to rowing — can sign a contract to sell merchandise through the school’s NIL Store. Because every NIL item is made-to-order, Campus Ink doesn’t lose any money by offering shirts for a third-string linebacker or backup soccer goalie.

But processing all of this — and growing this fast — is a massive undertaking. Campus Ink now has 76 full-time employees, up from 15 pre-NIL, and is about to outgrow its space. Farag and Swisher are looking at facilities that would allow them to at least double the number of presses for customized NIL orders. Two Decembers ago, they had deals to sell merchandise for 750 athletes, less than a tenth of the current total. This month, they announced they had paid out $1 million to athletes in a little over two years.

And before NIL? Farag and Swisher may have glanced at the title game on TV, otherwise discussing a bulk order from a fraternity, for that charity run, for those sweatshirts and … does this fabric feel right to you?

Before, they each had dreams for the company. The dreams just weren’t quite so big.

‘I’m sending you this money’

Campus Ink’s inner circle watched the end of the college football season in the Jedd Shed, the man cave/guesthouse Swisher built next to his home in Urbana. It has a golf simulator, a basketball hoop and an embroidery shop where Swisher’s wife does her part for Campus Ink. Farag lived there for a bit, after he graduated from Illinois and bought into the company that once printed the shirts he designed and sold on campus. Swisher wanted Farag to think less about rent and more about building the business. Eventually, after buying out the third partner, that meant they couldn’t take the next steps alone.

Adam Cook, a groomsman in Farag’s wedding, left a stable job in the printing industry to run Campus Ink’s NIL wing. Sean Ellenby left the University of Maryland to be Farag’s director of marketing and communications. Then Sean Childers, or “Chilly,” moved from Florida to Chicago to head up their graphic design, which is why he kept his laptop open during the title game, fiddling with a Washington champions shirt that would never go on sale.

“Keep working, Chilly, I haven’t lost faith quite yet,” Farag said, smiling and twisting a strand of hair around his index finger. Washington trailed by two touchdowns in the fourth quarter. Cook went for a boneless wing but wound up with a celery stick. Soon, Farag lost interest and started picking through a pile of clothes behind the couch. Cook and Ellenby glanced at each other, grinning at the exact same thought.

This is how Farag’s brain works. He had moved to the next thing.

“Jedd, what material is this?” he asked, holding up an Indiana starter jacket with an intricate design. “Okay, okay, okay, everyone. It is officially basketball season. Let’s go, Purdue.”

Purdue is a consistent top seller, largely because of a very large player: 7-foot-4 center Zach Edey — who, as an international student subject to different NIL rules, can sell merchandise through Campus Ink but not promote it himself. But the NIL Store concept, of partnering with athletes, teams and schools to sell their licensed merch, first started at Illinois, when Farag signed Brandin Podziemski, now with the NBA’s Golden State Warriors, shortly after the NCAA permitted NIL deals.

Farag connected with Podziemski through a student in Campus Ink’s student designer program. At that point, Campus Ink ran e-commerce for a handful of national fraternity chapters. If a Little League or family reunion needed shirts in the area, there was a good chance they would have printed them out of what started as a cobbler shop on Illinois’ campus in 1947. Right after graduating, Farag told Swisher he wanted to buy into the business, seeing untapped technology as a bridge to new revenue streams.

But NIL? Selling jerseys or sweatshirts with college players’ names on the back? Farag knew nothing about it, at least until he signed Podziemski, then star center Kofi Cockburn, then the whole Illinois men’s basketball team.

“If you sell 100 shirts, you’ll make $1,000. That was always the thing,” Farag said, detailing how the revenue-share model is central to his pitch. “With jerseys, I paid them even more. … I didn’t really have systems in place. I was manually calculating everything on spreadsheets. But I was paying them really quickly. It was like: ‘Hey, that shirt drop did well. I’m sending you this money.’

“During [the 2021-22] basketball season, we made them about $100,000.”

That same winter, Farag sent The Email. He had seen on Reddit that Mark Cuban tends to respond at odd hours. So late one Friday night, Farag started typing up Campus Ink’s story and couldn’t stop. He laid out his vision, hatched over hours of conversations with Swisher and Cook. They would vertically integrate, mainly with in-house shipping and printing, allowing them to disrupt the market with their athlete-friendly revenue sharing model. Every NIL sale would include a cut for athletes, even with something like a championship shirt without a specific player’s name or number, for which Campus Ink often partners with a donor-funded collective that then distributes money to the school’s athletes.

With the athlete’s cut, the school’s cut and other costs, Campus Ink would operate with fairly thin margins. But if they sold enough, it could work. This was thriving at Illinois. They had the online platform to scale it to other schools. There was just one problem with Farag’s pitch to Cuban.

He didn’t … make a pitch.

“His first response was: ‘Why are you emailing me? To brag?’ ” Farag recalled. “I just forgot to say: ‘Do you want to invest?’ ”

Cuban, then the owner of the NBA’s Dallas Mavericks, initially valued Campus Ink at almost $5 million, leading him to offer $250,000 for 5 percent of the company, according to two people with knowledge of the terms. Six months later, he led a group investment of another $2 million, then made another investment for an undisclosed amount. There’s good reason for the life-size cutout of Cuban in the conference room in Urbana, where Farag works after his old office was needed for production purposes.

From the beginning, Cuban had a lot of thoughts, showing a personal investment beyond his financial stake. A graduate of Indiana’s business school, Cuban told Farag to not just consider the Hoosiers’ football and basketball players but their wrestlers, too. He stressed Title IX and focusing equally on male and female athletes. And, yeah, they also had some fun.

While pitching to schools, Farag found some bigger programs don’t want to strain their existing licensing partnerships by adding another merchandise company to the mix. Michigan is on that list, as are Georgia, Florida and Texas, among others. But rather than go quietly after Michigan declined, Cuban purchased the domain GoBlue.com, went on Fox’s “Big Noon Kickoff” and told Michigan fans there was a surprise at that link. Once they clicked it, they were redirected to Indiana’s NIL Store. Michigan sent a cease-and-desist letter. Farag accepted he would probably never work with the Wolverines.

As for what has made Campus Ink thrive in a crowded market, Cuban said via email: “Personal attention to the people who do the work at schools and to the athletes. The big guys look at numbers first, people second. Campus Ink is all about the relationships they have.”

A license agreement with a school does not guarantee that every one of its athletes signs a contract with Campus Ink. It has Iowa as one of its schools but not Caitlin Clark on board. It has Ohio State but not NFL-bound wide receiver Marvin Harrison Jr. Two of its biggest names are Edey and Connecticut women’s basketball star Paige Bueckers, with basketball outselling football because of an emphasis on marquee players (and because their faces aren’t obscured by face masks on TV). On Jan. 8, a few hours before Washington and Michigan kicked off, Farag and Swisher stopped by a tall stack of Edey hockey jerseys, which have been extremely popular among Purdue fans.

Hearing the time it took for them to arrive from overseas, they both nodded, content. Farag then rubbed one of the jerseys, as he always does, and stared at the ceiling while taking the fabric in.

“You know, there’s the part we try not to talk about,” Swisher said with a subtle wink. “If, for some reason, Congress or the NCAA decides none of this should be allowed anymore and, poof, all this goes away tomorrow. But Steven doesn’t like that.”

“It’s not happening, Jedd, so we can talk about it all you want,” Farag said, laughing like a son might at his dad’s corny joke. “Things will change, but we’re built for the long haul.”

The championship game ended, Washington lost, and there would be no huge printing run of championship shirts in the morning. Farag, Swisher and Cook would tour a potential new facility, calculating what it might cost to drop lights closer to the production floor and heat the massive space in the winter. They would then have a meeting about a possible brick-and-mortar pop-up on a Big Ten campus during March Madness. Business would roll on.

But first, Farag drove to his apartment in a steady snow, the storm filling every inch of his windshield. He’s used to being in the car, alone with a podcast or his thoughts about where to steer Campus Ink next. For close to a decade, he has driven the 2½ hours between Urbana and Chicago once a week, sometimes twice. He now lives in Chicago with his wife, Carson, and their two French bulldogs. He’s learning to balance work and everything else. He’s trying, at the very least.

Yet there are so many people counting on Farag, himself included. He recently listened to Walter Isaacson’s biographies of Steve Jobs and Elon Musk, wondering how their childhoods shaped their approaches to business. Growing up, Farag liked building with his hands and solving problems. When he had a paper route as a teenager, he outsourced blocks to younger kids so he could hit more houses. His two older sisters are brainiacs — one a lawyer, the other a doctor — leaving engineer for him until he wasn’t any good at school.

“So this thing, this baby of mine, it has to work. I mean, this has to be absolutely killer,” Farag said. “I couldn’t cut it as an engineer. But I am going to keep figuring this out.”

The snow kept falling, slicking the road in front of him. At the same time, he hit his wipers and the gas.

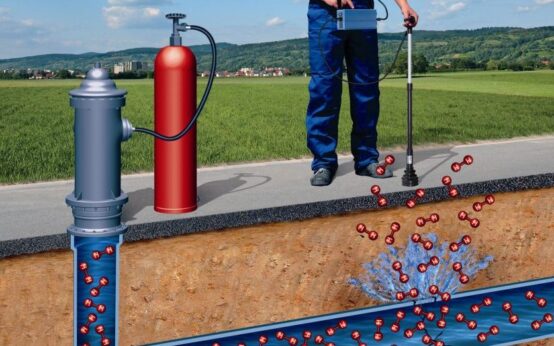

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024  Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven

Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven  Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez

Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez  Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today

Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today