And then the Facebook message landed.

“We have a 6 figure financial/NIL opportunity for you,” the messenger wrote, identifying himself as a former college quarterback and representative of a “data & analytics firm” called Big League Advantage. “Would love to discuss more if you’re interested.”

It was a fortuitous if fraught time for college athletes. The U.S. Supreme Court had ruled the year prior that athletes could no longer be deprived earnings from their personal brands, enshrining their so-called “name, image and likeness” (NIL) rights. Lawmakers, universities and the NCAA were scrambling to codify NIL policies as hefty checks began rolling in. Suddenly permitted to earn money for their stature, college athletes started showing up on television commercials, at trading card shows and at whatever marketing events sponsors could come up with. Companies rushed in to associate themselves with a new generation of rising stars.

Dexter wrote back and learned the details of a unique offer. BLA, as the firm is known, would pay him $436,485 immediately, according to the resulting contract. In exchange, Dexter would fulfill the sort of services typical of NIL deals: signing autographs, making appearances and posting branded content on social media.

But there was a catch that made the offer different from other deals emerging at the dawn of the NIL business. BLA sought much more than the right to use Dexter’s name, image and likeness. It wanted a cut of his future income: If Dexter made the NFL, he would have to pay 15 percent of his pretax salary to BLA. For the entirety of his NFL career.

Making sense of the deal meant navigating a nascent and disjointed system designed, theoretically, to help athletes make potentially life-changing financial decisions. A lawyer associated with a group of university boosters expressed concerns about the agreement, records and interviews show. But the UF official whose job it was to vet such deals gave it an unreserved green light, calling the offer “solid” and “legal.”

On May 17, 2022, eight days after the birth of his first child, Dexter signed with BLA. His financial woes eased, he turned in a solid junior season and, the next April, the Chicago Bears selected him 53rd in the NFL draft. Sitting on a couch at home beside his mother, fiancée and baby boy, Dexter broke into joyful tears.

An email from BLA’s attorney arrived soon after, reminding him of his obligation to the company. Dexter’s four-year rookie contract would be worth up to $6.72 million, more than $1 million of which he would owe to BLA.

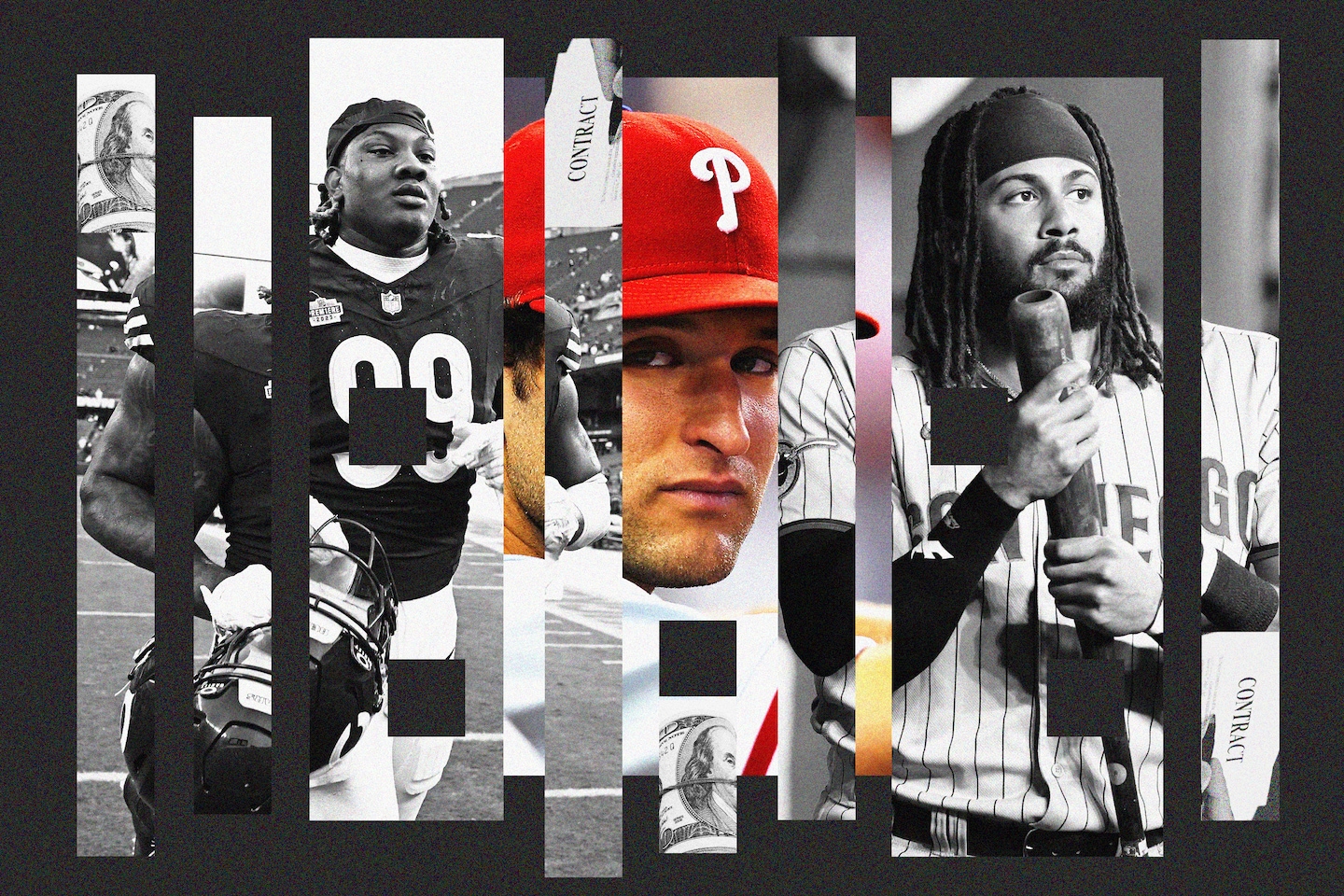

Professional sports have long been awash in financiers hoping to capitalize on the upside of rising athletes. But few if any firms have cut as many deals, and courted as much controversy, as BLA.

In its eight years of existence, BLA has signed roughly 600 minor league baseball players, including Dominican superstar Fernando Tatis Jr., who owes BLA a portion of his $340 million contract with the San Diego Padres. The company is the product of a brash former professional baseball player, Michael Schwimer, who has simultaneously dabbled in selling sports-betting advice to gamblers and analytics services to top college teams. But the legality of BLA’s business model, experts and lawyers in the field say, has never been fully tested, and the company has now forged a collision course with an NIL industry already plagued by scandal and legal uncertainty.

Dexter is one of at least 10 college football players to sign an agreement with BLA, according to the company’s website and social media postings. Five are still in school and five are in the NFL, with contracts worth an estimated $30 million. Dexter has claimed in a lawsuit against BLA that his deal was illegal, including that it violated Florida state law at the time that barred NIL contracts from having ramifications beyond a player’s college career.

Schwimer called Dexter’s allegations “ludicrous,” and BLA has filed motions seeking to move the dispute to confidential arbitration. Dexter didn’t respond to interview requests. His attorneys said he hesitated to file the lawsuit for fear it would become a distraction during his rookie year but moved forward in hopes of holding the company accountable.

“The egregiousness of this contract speaks for itself,” said Nicholas Patti, one of Dexter’s lawyers. “This is much bigger than Gervon Dexter. He can become a pioneer and somebody who has the means to not only protect himself but protect others from this in the future.”

Florida changed its NIL law last year to remove the prohibition on deals extending beyond a player’s college career. But the Dexter deal still drew criticism from one of the architects of the legislation.

“I consider that a predatory loan,” said Chip LaMarca, a Republican member of Florida’s House of Representatives. “It would have violated our legislation when he left the university.”

In an interview, Schwimer said LaMarca’s comments were “completely and totally inaccurate.” BLA’s agreements are investments, not loans, Schwimer said, and they can offer much-needed lifelines for athletes otherwise discarded by ruthless job markets.

But he also acknowledged that BLA has put NIL deals on hold until the dispute is resolved, blaming “massive brand damage” caused by Dexter and confusion among university officials as to whether the contracts are legal.

The Gaylord Opryland, a hotel complex under a massive glass atrium in Nashville, hosted baseball’s winter meetings last December, serving as a biodome for all of the sport’s professional creatures: executives, reporters, agents, players and, hustling from one hotel room meeting to another, Michael Schwimer.

He wandered the grounds on a Monday morning, holding court on why his business model offers an answer to the wealth gap in America; how his analytics department is the envy of all 30 MLB teams; and his plans to buy an NFL or NBA team, or both.

Looking for a quiet place to talk, he strode through the doors of an area reserved for media members. A security guard asked for his credentials.

“I’m a player,” Schwimer declared. The elderly guard took him in: 6-foot-8 with a mop of curly hair, workout clothes, Jordans and a Rolex. He let Schwimer pass with a shrug.

It was — Schwimer’s specialty — arguably true. He’s 38 now and hasn’t played in more than a decade, but he once suited up for the Philadelphia Phillies. A player in “the bottom 10 percent of talent,” he said, he made it to MLB, where he eked out a two-year career, by creating his own statistical models to outwit batters.

“I think I struck out about 15 per nine innings,” Schwimer said, exaggerating his minor league strikeout rate by more than three whiffs a game.

Before turning pro, Schwimer had studied sociology at the University of Virginia and interned at a hedge fund. So after he retired, he said, he pitched a Rolodex full of fellow country club members on the idea of an investment firm that would place smart bets on baseball prospects.

By 2016, at least 15 investors had signed on, said Michael Bryan, BLA’s former chief financial officer, who called it a “fun alternative investment that doesn’t correlate to the stock market.”

To help round up athletes, BLA launched a network of representatives throughout the minor leagues. Some are active players pitching the company to their teammates in pursuit of a commission. Schwimer says his company is “by players, for players,” and claimed that the resources and connections that go along with a BLA deal give athletes a higher probability of success.

“BLA is the one taking a major risk investing in you,” said Jack Labosky, a former player coordinator, echoing the pitch he used to make. “They’re in it with you. They want to see you succeed as much as you want to succeed.”

With firsthand knowledge of baseball’s feast-or-famine economy, Schwimer fully expected to lose money on most deals. But BLA’s first round of investment also proved the upside of that model by hitting on a human jackpot: Tatis.

BLA signed Tatis following the 2017 baseball season. By then, Tatis was considered one of the top 10 prospects in the sport. The San Diego Union-Tribune declared him a “cornerstone for the franchise’s future.”

But in Schwimer’s telling, Tatis “wasn’t a big prospect” when BLA first offered him the deal during the 2017 season, or when Tatis accepted it later that year. He credited BLA’s analytics department, which includes young data scientists poached from MLB, NFL and NBA teams, with discovering Tatis’s potential. “Nobody thought this kid was good,” Schwimer said.

Schwimer described the process of signing Tatis as a months-long courtship, including a dinner with his family, with the ballplayer’s agent having little to no input in the “family decision” made primarily by Tatis and his father, former MLB star Fernando Tatis Sr.

After signing the deal, Tatis spent just one more season in the minors before making the Padres’ 2019 Opening Day roster, triggering his first payments to the company. In a video posted to BLA’s website, Tatis Sr. vouched for the company, declaring, “BLA gave us a better quality of life.”

The video identifies him as a “BLA Ambassador.” Schwimer hedged when asked if the father was paid for the video. The elder Tatis expressed all the same compliments to BLA “at times where he was not compensated by BLA,” Schwimer said. “We can move on to the next question.”

Tatis is one of hundreds of ballplayers BLA has signed from Latin America, primarily the Dominican Republic, many of whom already saw a significant portion of their signing bonus siphoned away by hometown trainers.

“That population of player, more likely than not, is going to have a need, so it’s an easier clientele for BLA to go after,” said Storm Kirschenbaum, a baseball agent who estimated that 25 of his clients signed with BLA.

But Schwimer disputed that. “Latin players need it way, way, way less,” Schwimer said. “Do you know how far dollars go in the Dominican Republic?”

Schwimer acknowledged that BLA often bypasses players’ agents in Latin America, but only at the insistence of the athletes. When a player doesn’t involve his agent and doesn’t have a lawyer, Schwimer said, BLA offers a list of Spanish-speaking attorneys to look over the paperwork. Schwimer wouldn’t provide the list but said it includes attorneys who are also baseball agents and have clients signed to BLA.

One of them, Rafael Antun, told The Washington Post he has looked over dozens of BLA contracts but doesn’t advise players on whether the agreements are a good deal.

“It depends on how the pots are in your house,” Antun said, paraphrasing how one player described the decision to him. “Is your family eating? Is everyone healthy?”

In 2018, Dominican catcher Francisco Mejía sued to get out of his BLA deal, saying he signed while desperate to secure medical care for his ill mother. Among his claims were that BLA hired a lawyer to represent Mejía but he really “served as BLA’s lawyer.” Schwimer called Mejía’s complaint “full of lies.” The lawyer at Mejía’s signing did not respond to requests for comment. After BLA filed a counterclaim, Mejía dropped the lawsuit and issued an apologetic statement.

Controversy over the company has not dampened enthusiasm by its investors, who now number in the hundreds. SEC filings show that BLA has recently required a minimum investment of $1 million, though Schwimer said it makes exceptions. According to Schwimer, BLA has given just under $250 million to players while making back roughly $40 million.

That return will surely grow as top young players reach free agency. BLA’s website, which only lists athletes who agreed to be publicized, touts Cincinnati Reds phenom Elly De La Cruz, Miami Marlins all-star Jazz Chisholm Jr. and Washington Nationals catcher Keibert Ruiz as clients.

The sports agents who negotiate some of the biggest contracts tend to be BLA’s most outspoken critics.

Joel Wolfe, who has negotiated massive deals for stars like Giancarlo Stanton and Nolan Arenado, said he has asked BLA not to pitch its “loan schemes” to his clients, describing the company as among the “vultures that come circling” professional athletes. Scott Boras, who has represented a laundry list of superstars, also derided BLA’s deals as “usurious.”

“I do not find these companies to be anything other than individuals who are taking advantage of, for the most part, people in international markets who have little or no sophistication and a great deal of need,” Boras said in an interview.

Schwimer said it was unsurprising that top agents would criticize a business model designed to help minor leaguers. And he said that while Boras talks tough about BLA, his firm is more amenable in private. He shared with The Post emails to BLA from agents employed by the Boras Corporation that showed them soliciting offers for clients. “Wanted to check in” about a player, a Boras agent wrote in one of the emails. “Is he a player of interest for a potential equity deal?”

Another email showed that a Boras executive helped a client sign a BLA deal as recently as January. Schwimer shared the emails with the condition that the agents and players not be named.

Boras said that the emails were examples of the firm’s “very, very few” clients who asked to pursue such deals against his advice. “My job is information; my job is not decisions,” Boras said.

De La Cruz, a Boras client, signed with BLA when he was with a different agent, according to Boras. Speculation has already begun about what kind of nine-figure deal De La Cruz could command in free agency in a few years. But Schwimer downplayed De La Cruz’s chances of success. “All the top prospects always look like good players,” Schwimer said. “I love Elly … but sadly, math is math.”

BLA’s emphasis on the riskiness of its deals helps distance it from the allegation, vociferously refuted by Schwimer, that the company is simply doling out loans.

“BLA is at a very real risk of losing all capital paid to the player, which is very different from the financial position of a bank or other lender,” BLA general counsel Joseph Turo said in a letter to The Post.

The contracts players sign are explicit, too, using bold letters in English and Spanish. “This is not a loan and you understand that this is not a loan,” reads one contract.

But such language does not determine whether a contract is actually a loan, said Diane Ring, a Boston College Law School professor who has studied similar companies in and out of sports.

She referred to a controversial recent initiative by Purdue University, called an income share agreement, in which it covered the costs of higher education in return for a percentage of a student’s future earnings. Purdue’s contract with students said it was “not a loan.”

But the U.S. Department of Education later issued a directive that income share agreements in education were, in fact, student loans — and subject to the same laws and requirements. Purdue suspended its program.

Ring called the decision the “closest” thing to official guidance on whether income share agreements should be considered loans.

Schwimer said his business model is nothing like Purdue’s because it loses money on most contracts and only invests in a single income stream: a player’s salary at the top of their sport. And Ring acknowledged that it’s “not crazy for them to say that their business model looks different. Whether that’s different enough not to be a loan — I don’t know.”

Schwimer did himself no favors with the company’s initial name: Big League Advance. It wasn’t until 2022, as BLA forged its expansion into college football and other sports, that it replaced the word “advance” with “advantage.”

Schwimer said he was late to realize the word was a synonym of loan. “That’s how big of an idiot I am,” Schwimer said.

BLA’s best-known predecessor was a start-up called Fantex, which arrived a decade ago with an audacious plan that chief executive Buck French called “fantasy sports on steroids.” But the company effectively went out of business within four years, court records show, leaving a trail of disgruntled ex-clients.

That included former NFL receiver Mohamed Sanu, who shelled out $1.93 million to Fantex — $370,000 more than he received in a lump sum less than five years earlier, court records show. In late 2021, a California judge ordered Fantex to pay Sanu $1.1 million, and voided his contract with the company, following an arbitrator’s finding that it illegally acted as his agent. The following year, an arbitrator ruled that another Fantex athlete, NFL receiver Allen Robinson II, no longer had to make payments to the company, citing its “negligent misrepresentation” of its plans.

French did not respond to requests for comment. After Fantex, he formed X10, a private equity fund investing in the future earnings of professional athletes using what it calls “Income Purchase Agreements,” according to court records.

X10 is now, along with BLA, one of the most prominent companies in an increasingly crowded field. A constellation of other companies orbit professional athletes, offering upfront sums in return for a percentage of earnings or other compensation if the player succeeds, with little transparency or regulation.

The start-up Finlete advertises that it signed a contract with a teenage Dominican ballplayer for 10 percent of his potential MLB earnings and is offering shares to online investors. RockFence Capital gives out loans that ballplayers only have to pay back if they are in the major leagues. It shrouds its interest rate even from the insurers who underwrite its deals, court records show. And because these companies tend to require that all legal disputes go to confidential arbitration, the public often does not hear about them.

Among those calling for regulation of the industry: Schwimer. Beginning in 2018, BLA lobbied Delaware lawmakers to pass a bill Schwimer said was written to “protect players.” The Professional Athlete Funding Act sought to regulate what it called a “player brand agreement.” The bill would codify that such deals are “valid, binding, and not unconscionable” — and “not a loan.”

Delaware lawmakers passed the bill in 2019 and sent it to Gov. John Carney for approval. The unions for players in three leagues — MLB, NFL and MLS — urged Carney to veto the bill. BLA, meanwhile, donated $1,000 to his reelection campaign the summer the bill was on his desk, records show. Carney declined to sign it into law.

While attempting to reinforce the legality of one revenue stream, BLA diversified into others. Schwimer led a short-lived subscription service, called Jambos Picks, offering betting advice on college and pro sports. He also contracted with at least two top university men’s basketball programs — Duke and Alabama — to offer data analytics services through a company called Sports Analytics Advantage, or SAA.

Schwimer shared with The Post a video of Duke men’s basketball coach Jon Scheyer singing praises of “this guy Schwim … I’ve learned a lot from him.”

Of Alabama men’s basketball, Schwimer said: “We run the whole program. We do all the transfers. We do all the game style, we tell them what plays to run — we do everything for Alabama.” SAA’s contracts with Alabama confirm the company’s mandate to assist with everything from game management to recruiting. Alabama did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Schwimer brushed away potential conflicts by saying all of his companies are “completely different entities,” comparing himself to Elon Musk running Tesla and SpaceX. Corporate filings, and SAA’s contract with Alabama, indicate that SAA and Jambos Picks are subsidiaries of BLA.

SAA’s Alabama contracts, which The Post obtained via public records request, show the company is compensated mostly by how well the team does in the NCAA tournament. Alabama was ousted in the Sweet 16 round during last year’s tournament and SAA didn’t hit any performance incentives, earning a total of $50,000, according to the terms of the contract.

But this year has been a different story. Schwimer negotiated better terms for SAA, including $100,000 upfront. Alabama has made it to the Final Four, earning SAA $65,000 in bonuses so far. If Alabama beats Connecticut on Saturday, SAA will earn a $40,000 bonus, and if the team wins the championship game, Schwimer’s company will receive an additional $350,000, according to the contract.

Schwimer initially acknowledged BLA had signed some college basketball players. He declined to answer more questions about its investments in that sport, however, except for to say that BLA had not signed any basketball players at Duke or Alabama.

In contrast to baseball and its labyrinthine minor leagues, the route to the NFL for a young football player is more direct. Top-ranked high school players are funneled into elite college programs that act as a reliable conveyor belt to the NFL draft.

But until July 2021, BLA was unable to tap into this more predictable pipeline to professional riches. College athletes were barred from entering into financial agreements involving their sports. After the Supreme Court’s ruling, that suddenly changed.

Schwimer maintains that by wading into football, he was gambling on even “more of a crapshoot” than baseball — simply because of the higher injury risk. But outside of potential injury, Gervon Dexter appeared a near lock to soon be in the NFL when he attracted BLA’s attention less than a year after the Supreme Court decision. He was a former five-star high-schooler about to begin his junior season starting at Florida, after which he could expect to be drafted.

When pitching college football players, Schwimer said, he emphasized that financial security would improve their chances of making it to the NFL and excelling there. It’s one of BLA’s central claims; an investment brochure filed with the SEC boasts that the money lets players “train year-round, live in more comfortable conditions, and otherwise adopt a healthier, more motivated and more active lifestyle.”

That pitch does not move officials overseeing some NIL collectives, the groups facilitating payments to athletes and guiding them through the process. “If an athlete asks our advice, we do not encourage them to enter into those types of contractual arrangements,” said Matt Hibbs, who runs Classic City, the collective connected to the University of Georgia.

“From my understanding, they are not really in the ‘NIL’ business,” said Spencer Harris, executive director of House of Victory, which supports the University of Southern California. “It’s not something we’d encourage any of our athletes to do.”

Schwimer responded that collectives have “absolutely no say” in whether his contracts fit the definition of an NIL deal. “The schools determine if NIL deals are legal and compliant,” Schwimer wrote in an email. “USC has already approved our deals as legal and compliant NIL deals.”

Star defensive end Korey Foreman signed with BLA when he was with USC, before transferring to Fresno State. His financial adviser, Mike Ladge, said he couldn’t comment specifically on Foreman but that such deals are approved by the university. USC did not respond to requests for comment.

Ladge described BLA deals as a financial tool that, if used properly, can give student athletes access to resources like improved training and medical care. “Are you really going to be upset if you actually make $20 million and you have to pay back, you know, $2 million of it?” Ladge said. “You’re still set for life, but if you never got that money, you never maybe would have made the $20 million — you wouldn’t have got in the league.”

And Schwimer found a receptive audience at the University of Florida, a program whose short history in the NIL era has been plagued by scandal.

BLA offered deals to nine Gators football players, according to Schwimer, but Dexter was the only one to accept. In court filings, Dexter said he had a lawyer review the contract before he signed it. That lawyer, according to multiple people with direct knowledge of the matter, was Darren Heitner, the UF-educated outside counsel to Gator Collective, the university’s booster group.

Heitner agreed the upfront payment could protect Dexter financially. But he also expressed reservations to Dexter about the deal, according to a person with knowledge of their exchange. Heitner asked Dexter if he could accept a smaller lump sum in return for a lesser percentage of his potential NFL salary. BLA allows athletes to sign for as little as one percent of their future earnings and as much as 15 percent, Schwimer said.

And the lawyer advised Dexter to double-check the agreement’s legality with the university’s athletic department. In addition to the state law barring NIL agreements lasting longer than a player’s college career, UF’s guidelines also stated that a contract’s duration “may not extend beyond participation in athletic program at institution.”

As Heitner advised, Dexter did present the deal to a UF official. That official, Marcus Castro-Walker, had a consequential job title but no legal background. In his previous job as director of player development at the University of Nebraska, Castro-Walker was best known for wearing sunglasses while pacing behind the head coach on the sidelines. He was hired in December 2021 to be UF’s director of player engagement and NIL, believed to be the first of his kind in university athletics.

In a promotional video posted by UF, Castro-Walker said a “large part” of his job is to “make sure that these young men are understanding contracts they’re signing.”

Castro-Walker offered a blunt assessment to Dexter of the BLA proposal. “Gervon, the contract is solid,” Castro-Walker wrote in an email reviewed by The Post. “Everything from an NCAA compliance standpoint is legal.”

Castro-Walker and the Gator Collective were embroiled in one of the NIL era’s highest-profile scandals in the months after Dexter signed with BLA. Jaden Rashada, a top quarterback prospect, backed out of his commitment to the school after claiming that the collective affiliated with the Gators failed to come up with the $13 million it had agreed to pay him.

Days after the NCAA announced it was investigating, UF confirmed that Castro-Walker no longer worked there.

The Gator Collective has since disbanded. Castro-Walker did not respond to repeated requests for comment. Heitner declined to be interviewed. UF Athletic Director Scott Stricklin did not respond to a list of questions nor an interview request.

Meanwhile, NIL regulations have since only continued to shift. This year, a federal judge ruled that the NCAA can no longer prevent players from negotiating NIL deals before enrolling at a school. The ruling will allow NIL deals to be dangled as a recruitment tool. In the absence of federal legislation setting uniform terms across the country, schools, athletes and companies are left to abide by a patchwork of state laws.

In Florida, instead of tightening regulations in the wake of the NIL scandals there, lawmakers have loosened them. Florida amended its NIL law last year to erase the majority of its initial regulations, including the clause central to Dexter’s claim that prohibited deals that “extend beyond” a student’s college tenure.

LaMarca suggested that the deregulation was necessary for recruitment. “It was to streamline the law to be as competitive with the other states as possible,” LaMarca said. “We ended up restricting our athletes from accessing more opportunities that other states have, so we took guardrails down.”

Today, seven states have laws barring NIL deals that “extend beyond” college eligibility.

In an interview, Schwimer contended that the clause was irrelevant to BLA’s legality anyway. Dexter’s contract, filed in court, referenced two terms: an “initial term” that lasted while Dexter was in college and an “extended term” that kicked in when he made it into the NFL. Schwimer claimed that the contract language worked around Florida’s NIL regulations.

Dexter’s lawyers disagree. “There’s one contract that was signed, and it was signed when he was in school,” said attorney Caleb Diaz, who called Schwimer’s argument “semantics.”

Schwimer said Dexter’s lawsuit caused BLA to shelve offers for a long list of college athletes — including Florida State quarterback Jordan Travis, who the company “had millions of dollars for” and is now recovering from injury.

“Because of the Gervon Dexter lawsuit, he never even got to hear an offer and now he broke his leg,” Schwimer said of Travis. “Now what’s going to happen to him?”

Schwimer predicted that he would prevail in court, which he called the “saddest part of my job.” He blamed players’ agents or lawyers for misleading them into thinking they can challenge his company’s model.

“They lose, they pay legal fees, and they pay interest,” Schwimer said. “And they’re going to keep doing it because people want to make names for themselves. And all it does is hurt the athlete.”

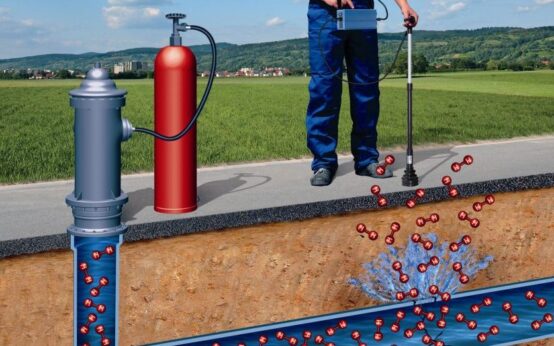

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024  Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven

Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven  Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez

Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez  Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today

Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today