“The Tennessee judge apparently granted the injunction,” a reporter said.

“What did the Tennessee judge do?” Baker asked, processing in real time.

“He granted the preliminary injunction,” the reporter answered.

“Well, I don’t have a comment on that,” Baker said. “Because, obviously, it’s news. Sorry.”

For more than an hour, Baker mostly declined to discuss legal challenges facing the NCAA. And with the Tennessee case specifically, he would have to debrief with lawyers before making any statements (through his public relations team or otherwise). Friday’s ruling, issued by District Judge Clifton L. Corker, is a broadside against the NCAA’s existing NIL policy and boils down to this: For now, the NCAA can no longer prohibit collectives using NIL money to entice athletes to pick a school, which generally happens in football and men’s basketball recruiting.

The preliminary injunction takes effect immediately, applying while the NCAA, Tennessee and Virginia keep battling on the issue in court. And while it doesn’t immediately reach nationwide, the NCAA is already reviewing potential policy changes and is expected to communicate with its member schools soon. With similar cases in the past, the NCAA has tweaked or dropped rules in favor of consistency.

What led to all this in the first place?

A key part of the NCAA’s interim name, image and likeness (NIL) policy is that under no circumstances can money be used as an “inducement” for an athlete to pick a school. This happens all the time, of course, with very few instances of enforcement. But when the NCAA investigated the University of Tennessee for potential recruiting violations, the attorneys general in Tennessee and Virginia challenged this rule in court on the grounds that limiting how athletes earn NIL money is a violation of antitrust law.

Tennessee’s endorsed collective, Spyre Sports Group, reportedly struck an $8 million deal with five-star quarterback Nico Iamaleava before he enrolled, attracting the NCAA’s attention. (Collectives, while involved in roster building and created to raise money to pay players through NIL deals, are not officially part of any university or athletic department.)

Corker’s ruling, then, made it so the NCAA cannot enforce its own rules (for now) or attempt to regulate the NIL market with the threat of recruiting violations. The ruling also doesn’t bode well for the NCAA’s enforcement power long term.

In practice, this means a representative of an NIL collective can fly to meet with a recruit, then offer him a six-figure salary that hinges on the athlete doing a handful of appearances and social media posts for various charities. They could even agree on the terms in writing, if they choose. And if that doesn’t make it sound as if anything has changed, the school connected to that collective doesn’t have to worry about potential sanctions that could penalize its program or affect the athlete’s eligibility in the future.

In the ruling, Corker wrote that “while the NCAA permits student-athletes to profit from their NIL, it fails to show how the timing of when a student-athlete enters into such an agreement would destroy the goal of preserving amateurism.”

So the case, while ongoing, is certainly not moving in the NCAA’s direction. The quiet parts of NIL, often said out loud in recent years, can now be shouted from the rooftops.

On Friday afternoon, while Baker was still in an eighth-floor boardroom off Dupont Circle, Jonathan Skrmetti, Tennessee’s attorney general, said in a statement: “The court’s grant of a preliminary injunction against the NCAA’s illegal NIL-recruitment ban ensures the rights of student-athletes will be protected for the duration of this case, but the bigger fight continues. We will litigate this case to the fullest extent necessary to ensure the NCAA’s monopoly cannot continue to harm Tennessee student-athletes. The NCAA is not above the law, and the law is on our side.”

Then the NCAA issued its statement Friday evening, saying: “Turning upside down rules overwhelmingly supported by member schools will aggravate an already chaotic collegiate environment, further diminishing protections for student-athletes from exploitation. The NCAA fully supports student-athletes making money from their name, image and likeness and is making changes to deliver more benefits to student-athletes, but an endless patchwork of state laws and court opinions make clear partnering with Congress is necessary to provide stability for the future of all college athletes.”

Baker maintains that, without congressional help, he cannot implement a new model that allows schools to pay athletes an unlimited amount of educated-related funds, enter into NIL deals with their athletes and choose whether to join a subdivision for programs that spend the most money on sports. This made congressional intervention a theme of his meeting with reporters.

The NCAA is still seeking a handful of federal measures, including: a preemption that would allow the NCAA’s NIL rules to supersede state laws, special status that would bar athletes from becoming employees and what Baker called a “narrow” antitrust exemption that would help shield the NCAA from current and future legal threats — such as the ruling in Tennessee.

At one point, the former governor of Massachusetts went down the list of those challenges, painting a clear picture of what the NCAA is up against. There is the House v. NCAA antitrust case in California, which could cost the NCAA and its members more than $4 billion in damages (in the form of back pay to athletes in football, men’s basketball and women’s basketball for the use of their NIL on television broadcasts).

There is the Johnson v. NCAA case, with the plaintiffs arguing that athletes should be considered employees under the Fair Labor Standards Act and paid for the time they spend on athletic activities.

Elsewhere on the employment front, a regional director for the National Labor Relations Board recently ruled that the Dartmouth men’s basketball team can hold a union election March 5. That process is only at its beginning, though it’s a small step toward college athletes being able to organize and collectively bargain with their schools. Then in California, the hearing against USC, the Pac-12 and NCAA — arguing that athletes are employees of their school and conference — resumes Monday.

Does Baker think the NCAA can win each of these challenges? Any of them? And if not, what’s next?

“I’m going to give the answer I usually gave people when I was governor when they would ask me about lawsuits, “Baker said Friday. “Which is: It’s not really a good idea to talk about lawsuits unless you’re in court.”

And what will he do if the courts rule against the NCAA before it can get help from Congress?

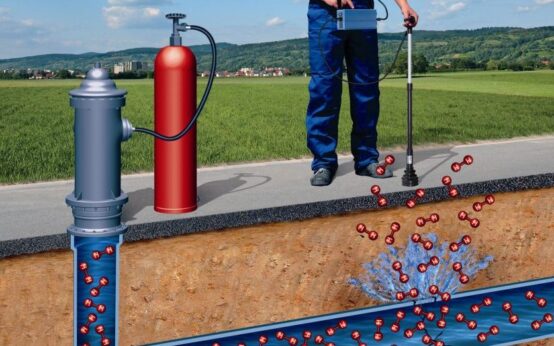

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024  Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven

Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven  Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez

Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez  Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today

Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today