The Banner is a start-up nonprofit newsroom focused on local accountability and civic impact and funded by hotel magnate Stewart Bainum, who tried to buy the Baltimore Sun before it was sold to a hedge fund in 2021. The outlet has 11 sports reporters, including two beat reporters for both the Orioles and Ravens. For Game 3 of the American League division series, it sent five people to Texas, an outlay that defies this age of media belt-tightening. (The Sun sent three.)

“I said at the meeting when they told us [five], ‘Is that too many?’” said Andy Kostka, one of those Orioles beat writers. “The Orioles are always joking, ‘How many Banner people are showing up today?’ ”

Sports were not part of the Banner’s launch, but the newsroom hustled to ramp up its coverage ahead of last baseball season. The Orioles are now the Banner’s third best subscription driver, after food and breaking news.

The Banner is one of several new start-ups that has emerged in recent years, hoping to build a business on local sports fandom. A new site in Oklahoma poached the state’s most popular newspaper columnists and wants to turn them into influencers; a live events and video podcasts company is now in four cities and backed by some $10 million in venture funding; then there are the handful of team-focused newsletters on Substack.

The efforts recall the early days of another local sports start-up: the Athletic, a subscription site that debuted in 2016 and was bought by the New York Times last year for $550 million. The Athletic marketed itself as a replacement for struggling local newspapers by putting beat writers on every pro and major college team in the country, then knitting together that local coverage to create a national outlet.

But at least part of the opening for these other companies is that the Athletic, as it looks to reduce costs, has pared back its local beats (and the expensive travel that comes with it) to focus on teams with larger fan bases. In a round of layoffs earlier this year, the Athletic cuts its Orioles writer.

The Athletic still covers some 100 teams across the country, and those cuts appear to be paying dividends. Publisher David Perpich told staffers on a recent all-staff call that the outlet is on pace to be profitable by 2025. For fans, there is a clear divide between teams that merit beat coverage and those that don’t, among them the Denver Nuggets, Miami Heat, Chicago White Sox and most colleges. They could be forgiven for wondering what coverage will look like if the economics don’t work for the Athletic and with local newspapers still struggling.

At the Banner, the audiences are not necessarily huge. Spring training stories were generating as few as 200 pageviews, Kostka said. But as the team took off last season, the audiences grew; good feature stories could generate around 10 new subscriptions — a look at Adley Rutschman’s grandpa, for example, and the drunk fan who threw a Shohei Ohtani home run ball back onto the field. The Banner has also exhaustively covered the twists and turns of the Orioles ownership and stadium lease sagas, breaking several stories about both. There is a belief that the combination of rabid fandom and proprietary coverage of local sports remains a good business.

“Fans care about their sports team,” said sports editor Chris Korman. “It’s what people talk about; it’s a huge part of being a Baltimorean.”

In Oklahoma, Sellout Crowd launched this year in another market after the Athletic pulled back. It poached the state’s two best-known newspaper sports columnists from the Oklahoman, Berry Tremel and Jenni Carlson, and are covering the Thunder and the state’s two biggest colleges. (The Athletic previously had beat writers for the University of Oklahoma and the Thunder.)

The premise is to connect those well-known reporters with local businesses. “The idea is what happens if you treat the sports content creators in traditional media like you treat influencers,” said Mike Koehler, the site’s founder. “Help them build brands, create their platforms, broker deals between them and sponsors and help with the monetization and distribution of their content.”

He said he is looking to expand across markets in the Big 12 and SEC.

Of the Athletic, he added: “I think the issue with the Athletic was they had local beat writers, but no local sales people. They didn’t realize that if you go to roofers and you go to car dealers and those places in town who are spending ad dollars around the sports team being covered, that they are also willing to spend dollars on content around those teams.”

(The Athletic, under Times management, now sells advertising. An Athletic spokesman added that though a team might not have a dedicated beat writers anymore, they are often still covered extensively by other reporters.)

Brandon Spano, a former radio host and media executive in Denver, launched a sports website in 2015, then relaunched it in 2019 as DNVR. In the past two years, he has raised more than $10 million in investments and has launched companion sites in Phoenix, Chicago and Philadelphia, part of what he’s calling the All City network. The model is built around daily video podcasts for every team in a market with a vibe more fan-centric than buttoned-up reporter. He’s hired established voices, including two Philadelphia Eagles writers from the Athletic, as well as popular fans from social media.

All City’s top source of revenue is ad sales, Spano said, while merchandise sales will be around $1 million for this year. Membership, or subscriptions, is third. The operations in Denver and Phoenix, he said, are profitable.

Then there is Substack. Christian Caple, a University of Washington beat writer, was laid off by the Athletic earlier this year. Six days later he launched his newsletter, offering essentially the same coverage of the Huskies. He charges $8 per month and $65 per year for a subscription and said in an interview that he is already making “significantly” more than he did as an Athletic staff writer; it certainly helps that Washington is undefeated, headed to the College Football Playoff and announced this year it was heading to the Big Ten next season. (Another former Athletic college football writer covers Auburn on Substack, too.)

Caple said he sees the model as replicable, but only in specific circumstances. There isn’t a ton of competition on the Washington beat, readers were conditioned to pay him from his years at the Athletic and he’s been covering the school for more than a decade.

Across the landscape, these entrepreneurs echoed similar advice, from diversified revenue streams to the importance of marketing dollars to leveraging already established writers that have preexisting relationships with fans (the latter was and remains a key pillar of the Athletic). But they also offer some hope that new coverage models can emerge for fans of teams outside the Yankees, Lakers or any NFL team.

“I wouldn’t be surprised to see more people take a swing at this,” Caple said.

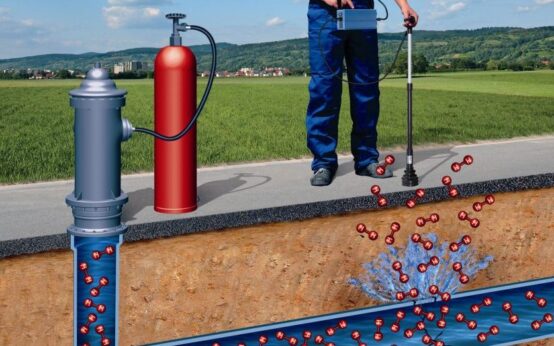

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024  Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven

Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven  Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez

Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez  Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today

Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today