This keyboard in front of him, it can read his mind in a way. It tracks his eye movements, using them to type words and sentences and then dictate in a synthesized voice that sounds like his own. The technology is popular among people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), the progressive nervous system disease that overturned Behan’s life in spring 2022.

Last winter, as Behan’s story became widely known, it grew into a basketball fairy tale, as the Cadets marched to a Washington Catholic Athletic Conference championship. Memories of that season remain vibrant as the coach’s illness progresses. Meanwhile, with the WCAC slate beginning in earnest this week, St, John’s has an interim coach and stars from its title team scattered across the country.

As Behan scans, the only noise inside his apartment is the rhythmic whir of the ventilator by his side. It keeps time in the quiet, pumping air through the tracheostomy tube connected to his throat. Breathing, just like speaking, is now beyond his control.

He sits in a recliner chair, a wall of televisions in front of him. There are six of them, in two rows, to provide as much escape as possible. He has always been a sports fanatic, and that has been especially true in sickness. From his chair he watches an endless stream of baseball, college football and golf. Now that its basketball season, he follows the college careers of his former players.

On this Monday night in late December, only one TV is on. The 6 p.m. edition of SportsCenter plays on mute, illuminating the dark room. In the corner sits a tree covered in ornaments and topped by a big red crab in place of a star. Christmas is a week away.

“I probably knew around the team banquet in early May,” Behan says after a few minutes. “Which, ironically enough, is pretty much the time that I found out I had ALS the year before.”

One year. After being diagnosed with ALS at age 34, Behan got one year to coach basketball. Those months were busy and long: Countless trips to Boston for treatment; a full basketball season; public appearances to raise awareness and money through the Behan Strong fundraising campaign. The schedule was never open and energy never came easy.

But on the court, everything fell into place. St. John’s had three stars, a selfless supporting cast, a dedicated coaching staff and something — someone — to play for.

The Cadets went 32-4, culminating in an dramatic 65-63 win over Paul VI in the WCAC championship. That game will be talked about in this region for a long time.

“I was proud of the way everything connected together,” Behan says. “They showed me the true meaning of embracing roles.”

But when the season was over, and there were no more games to play, a different reality set in. All great high school teams are defeated by time, bulldozed by the cyclical nature of the scholastic game. That championship-winning St. John’s team — memorable in so many ways — was gone in one offseason.

Donnie Freeman stepped out of the makeshift locker room assigned to his team in the back halls of DeMatha, ducking his 6-foot-9 frame through the doorway in a silver puffer jacket.

Freeman knew his way around this gym, had played plenty of games as a visitor on its red and blue floor. But in the minutes after IMG Academy’s 63-58 loss to Bullis on Dec. 10, Freeman was just waiting for his team to hit the road again.

It was mid-August when Freeman announced he would be leaving St. John’s for IMG, cutting a celebrated Cadets career short of a victory lap. He moved to Bradenton, Fla., and returned to the area in December for the National High School Hoops Festival, an annual showcase in Hyattsville. The Syracuse commit played in the blue and white of IMG, scoring 12 points as his team was upset.

“I had a lot of growing up to do,” Freeman said. “It’s been a good experience going off on my own and living on my own before college. But it’s an adjustment.”

He had come to St. John’s as a skinny kid with immense potential. Pre-teen growth spurts made him a guard in a center’s body, the kind of fluid rim-protector coaches crave. He earned varsity minutes as a freshman and steadily developed into a star.

By his junior year, he had two standout guards flanking him.

Daquan Davis, a hard-nosed guard from Baltimore, joined the Cadets before the season. He transferred from St. Frances, looking for more exposure in a key period of the college recruitment process. He knew he wanted to play in the WCAC; he just had to choose a school. He had noticed Behan at many of his AAU games, the former power forward towering over the crowd. Davis picked St. John’s and hoped for the best.

Malik Mack was in his fourth year on the Cadets, having worked his way back after missing his sophomore year with a torn ACL. By his senior season, he was an ideal veteran ball-handler — crafty and calm. Behan referred to him as the “heart and soul” of the team.

In the WCAC tournament — an always-tense three-day obstacle course that determines the league’s outright champion — Mack, Davis and Freeman each had a defining moment. In the semifinal against Gonzaga, Freeman hit a deep three with 19 seconds left to give his team a one-point win. In the next day’s final against Paul VI, Mack paced the team with 15 points and eight assists, hitting a step-back three with under a minute left to put the Cadets up by one. And after a Panthers free throw tied the score, Davis beat his man and laid in the game-winner with 3.8 seconds remaining.

“The chemistry was probably the main reason we were winning last year,” Mack said. “We had talent, but we maybe weren’t as talented as some other teams. … But everyone got along, everybody hung with each other off the court. It was a real brotherhood, and that’s what set us apart.”

Mack is at Harvard now, starring as one of the best players in the Ivy League. In the first month with the Crimson, he averaged 20 points and was named conference freshman of the week three times.

With three starters graduating and a potential coaching change coming, Davis and Freeman knew they were entering an offseason of uncertainty. Both players, having watched Behan’s health deteriorate, had a feeling their coach would not be able to return They had myriad options to leave St. John’s.

In the early summer, Davis was approached by Overtime Elite, a basketball league based out of Atlanta that aims to give high school players an alternate pathway to the NBA. Players are offered a salary if they forego college ball, or a future scholarship if they still want to maintain their collegiate eligibility.

Initially, Davis was not interested, but his family encouraged him to reconsider. He now spends his days training and playing games on the weekends as he weighs his college decision.

For Freeman, if Behan was returning to St. John’s, he was returning, too. There was no doubt about that. But when the coach missed team activities in June, the four-star prospect considered the possibility he could spend his senior season elsewhere.

In early July, he went to Georgia to take part in Peach Jam, the biggest event on the AAU calendar. That week, Behan was admitted to George Washington University Hospital with several complications from ALS, including pneumonia. The Behan Strong social media accounts posted updates, telling followers the coach was “fighting for his life.”

At Peach Jam, Freeman was recruited hard. Considering the strong connection between St. John’s and IMG Academy — which is led by former Cadets coach Sean McAloon — the Ascenders initially abstained from the chase. But when Freeman and his family decided a transfer would be best, the Florida school seemed like a comfortable destination.

Comfort is something all three players are seeking. Mack, Freeman and Davis have adjusted to new roles and new teammates, different goals and stakes. Basketball is still basketball, but it’s unclear if it will ever feel like it did last season.

“From the managers to the coaches to the players and everyone in between, that team was just locked in,” Freeman said. “And to come out with a championship, knowing what it took for us to get to that point, it was surreal. You can’t really put words on a moment like that. I’ll remember it for the rest of my life.”

Patrick O’Connor was named interim coach of St. John’s on Aug. 28, less than a week after Behan told The Post he would not return.

The 31-year old is lively and earnest, a former Division III forward at Washington and Lee who came to the District after college for a teaching residency. He arrived at St. John’s in 2016, serving as the coach of the freshman team as well as a varsity assistant under McAloon. When McAloon left for IMG a year later, O’Connor asked around about the supposed successor, a former Cadets assistant who had turned around the St. Mary’s Ryken program in Southern Maryland.

“Don’t worry,” a co-worker told him. “Behan is one of us.”

Behan kept him on staff, and the pair grew close.

“I had a really positive high school basketball experience, making some lifelong friends,” O’Connor said. “So I don’t want to be a college coach. I don’t want to be an NBA coach. I want to be a high school coach because I know it can be four of the most formative years of a young man’s life.”

O’Connor inherited a Cadets team with no seniors and no returning starters. Outside of transfer Omari Witherspoon, the Cadets did not add any experienced talent as they seek to defend a title in one of the country’s toughest conferences.

“We tell the kids phrases like ‘Be you’ and ‘Next is now,’ ” O’Connor said. “Those are just little things we say to them, but I’m also saying them to myself when I go home.”

The coaching staff also looks different this winter: Artie Bryant, a longtime Cadets assistant, died in September, leaving a second painful void on the bench.

For a team with so many new variables, St. John’s has fared well so far. They went 10-3 in December, handling opponents from far and wide as they proved a rebuilding WCAC team is often just as good as another league’s heavyweight.

O’Connor remembers last season as a whirlwind. From the staples — practices, tournaments and scouting trips — to the little things unique to his relationship with Behan, like when Behan’s hands started to fail him and O’Connor would help map out plays on the whiteboard or hold a water bottle as the head coach drank. There was no thought to the bigger picture. There was only finding a way to move forward, one game to the next.

When he thinks about the WCAC championship, he thinks about the final shot of the night. After Davis’s lay-in gave the Cadets a lead, Paul VI called timeout to plan a hopeful heave. It came from guard DeShawn Harris-Smith — the All-Met Player of the Year — and it looked good from the moment he released it.

Three years before, the Cadets had lost a regular season game to Paul VI on a half-court shot. Behan and O’Connor obsessed over that loss for weeks, talking through the best ways to guard against that heartbreak.

“Is this really going to happen again?” O’Connor asked himself when Harris-Smith released the ball.

When the shot caromed off the back rim, O’Connor turned to Behan and hugged him, burying his face in the taller man’s shoulder. They stayed like that for some time, unmoving and surrounded by joy.

“So many people had a hand in making last year a success, and I want to honor them by continuing that trajectory,” O’Connor said eight months after that night. “I want to make the school proud. And I want to make him proud, too.”

Sitting at Behan’s bedside on that late-December night — and every other night — is his wife, Nataly. They have been together six years and got married in August. Last winter, she could, without fail, be found in the first row behind the St. John’s bench, her eyes darting between the action on the court and the coach on the sideline.

It amazed her, what would happen to him while he was coaching. The passion he could summon, how different it was to the fatigue and pain she saw before and afterward. As the Cadets marched toward a title, those off-court moments grew more difficult. Behan’s form of ALS is familial, and several relatives, including his father, have died from it. From the moment he was diagnosed, he knew the passage of time would be his adversary.

At the start of the season, Behan’s main issue was fatigue. As the Cadets worked their way through conference play, more problems arose. His breathing became more labored, his hands functioned less. By playoff time, Nataly could detect a slur in his speech.

“But in the spring, that’s when everything got worse — from swallowing to his voice to breathing,” she said.

Away from the spotlight of the basketball season, the struggle became more intimate as it grew more difficult. The first major scare came in early July with the lengthy hospital stay. That’s when doctors mentioned switching from a BiPap mask — which helps push air into his lungs — to the ventilator.

He returned to the hospital in late October, staying for 18 days as he battled two pneumonia infections. Toward the end of that visit, the home ventilator was installed.

“I had to learn every single thing about it,” Nataly said. “I remember thinking ‘Am I going to be able to do this?’ The vent is my responsibility, even with the caretakers that are with us. So when I leave the house, I only ever go within a mile radius. I want to make sure I can get back here.”

The ventilator represented another responsibility and also more money. Over the last year and a half, the couple has dealt with the exorbitant costs of serious illness. Donations, collected on the Behan Strong site and a GoFundMe, are integral to his wellbeing.

In addition, the ventilator made any kind of travel more laborious. He has attended two St. John’s home games this season, a five-minute drive that requires of hours of preparation.

“People see him and say that he looks good. And he does,” Nataly said. “But it takes my whole family helping me out — eight of us — to get him ready. It’s a whole process. We want to make sure he’s safe. And that’s a lot.”

On Wednesday, Behan was courtside for the second annual Behan Strong Invitational, a three-game showcase to raise awareness and funds to benefit his care. At last year’s event, Behan led his team to a thrilling win over IMG, the first real sign that the Cadets had championship potential. This year, he entered Gallagher gymnasium just before the second game of the night, planting his wheelchair in the corner next to the St. John’s bench.

He received an ovation from the crowd, and as the starters were announced for Bullis and Jacks0n-Reed, each player ran over to greet him. Unable to extend his hand for a high-five, Behan would stick his foot out for each player to tap: A gesture, as much as he could muster, of encouragement and thanks.

Being back in the gym reminded him of the joys of last year. Of all the games Behan has watched from his recliner the past few months, that championship game is not one of them.

“It’s funny, I haven’t in a very long time,” he said. “But I had an urge the other day.”

When he does, he will see many of the sequences that already exist on a playback in his mind: Malik’s three-pointer, Daquan’s final drive, the buzzer-beater that didn’t go. What he won’t see on the film is the part of that night he thinks about most.

After O’Connor releases him from the hug, Behan is mobbed by more well-wishers. Nataly is there, crying happy tears. His friend Glenn Farello, coach of Paul VI, comes to shake his hand. There are TV cameras and students and sweaty players everywhere. It is a joyous mess.

At some point, a chair is fetched. Behan sits there for some time, surrounded by his school community. A reporter asks him how he’s feeling.

“It hasn’t sunk in yet,” Behan says, exhausted and elated. “But it will. I just don’t know when.”

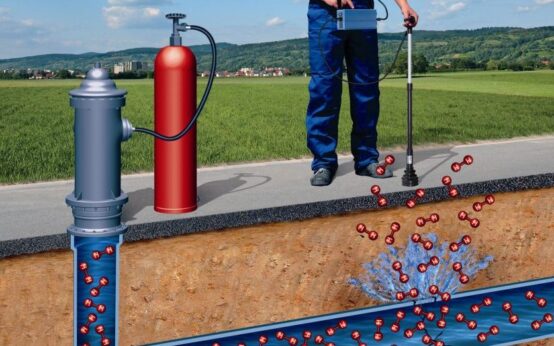

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024  Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven

Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven  Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez

Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez  Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today

Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today