A shrinking pee-wee league. Worried football moms. Even under West Texas’s Friday night lights, the sport is losing some of its glow.

“I love football. I watch the NFL. We go to the games. Believe me, I’m all-in on football,” said Leong, a lifelong educator who now is an administrator for the Abilene Independent School District. “But there is a part of me — I pray over every game, ‘Please keep these boys safe.’ We’re all more educated now.”

Nearly a decade and a half into football’s brain-injury crisis — from the initial studies linking the sport to CTE to the seemingly constant stream of CTE-related tragedies involving ex-players to the self-preserving response of the football industry — these are the choices and the accommodations that parents, and grandparents, still have to make regarding a sport that holds an unparalleled sway over American culture.

It is true even in West Texas, the actual and spiritual homeland of “Friday Night Lights.” Even here — where Tami Taylor, the fictional matriarch of that show, is less a character than an archetype — some folks’ relationships with football could best be described as complicated.

“You’re torn,” Leong said, “and you just wish there was an easier answer.”

And even Texas has not escaped the slow decline in football participation that has taken hold at the sport’s grass-roots levels.

Nationally, participation spiked in 2006, the same year the NBC adaptation of “Friday Night Lights” debuted. But it is down 17 percent since then, despite a rebound in 2022 as the country came out of the pandemic. Meanwhile, in Texas, while there are far more high school football players than in any other state, football participation is actually down by 12 percent over the past decade when adjusted for the growing number of public high-schoolers, a Washington Post analysis found.

For the men of the Leong family, there is no ambivalence: Football is and always will be king. Lyle Leong Sr., Kari’s husband, used the sport as a way to get out of South Central Los Angeles in the 1960s, winding up at Abilene Christian University before a brief run in the Philadelphia Eagles’ organization. He still coaches youth football in Abilene. Their son, Lyle Jr., starred at Abilene High and Texas Tech before spending time in the Dallas Cowboys organization, then playing one season in the CFL. He now is the head coach of Levelland (Tex.) High, about three hours northwest of Abilene.

“Football, for so many of us, especially Black families — it was our connection to college. Because we were betting on that college scholarship,” Kari Leong said. “That was so huge. It was like, ‘You’re playing football — because you’ve got to get to college.’ It was not an option: ‘You’re going.’ That was how we raised our kids. Football was, for so many of us, our ticket out.”

Still to be determined: the future pathways of the next generation of Leong boys. In Levelland, Lyle Jr. has vowed to keep his 4-year-old son, Kenzo, out of tackle football until he is 9 or 10. And in Abilene, 10-year-old Kingston, the son of the Leongs’ daughter, London, played in a seven-on-seven touch football league this season but is likely to move to tackle next year — despite his grandma’s reservations.

Near the start of this football season, Kari Leong sat next to Kingston and asked him if he wanted to play tackle football soon. The boy, predictably, said yes. So she asked if he was worried about getting hit in the head. Kingston said no and wrinkled his nose.

“He said, ‘Gigi, I’m not going to get hit in the head. I know how to avoid that,’ ” she recalled. “Most parents in my circle, we’re flocking to the seven-on-seven. I don’t worry when he goes off to practice. I don’t worry about him coming home with a concussion. … But whether he’s going to play tackle football? It’s a concern. Because I’m very concerned about CTE.”

She has often thought about what she would have done with Lyle Jr. back in the mid-2000s had she known then what we know now about football and CTE. Her conclusion: It’s probably better that she didn’t know. Lyle Jr. suffered one concussion that she was aware of, and a second that she suspects, and when he finally told her he was retiring from the sport, she said, “Oh, thank God.”

“I probably would have been very skeptical of him playing,” she said of the what-if question. “I probably would’ve lost that battle. But I would have been worried. I would have been worried so intensely.”

TEXAS HAS ABOUT AS MANY HIGH SCHOOL football players — 170,965 in 2022, according to the annual survey of the National Federation of High School Associations (NFHS) — as the next three states combined: California (89,178), Ohio (43,020) and Illinois (39,424). It is the land of $70 million high school stadiums and state championship games that routinely draw 40,000 or even 50,000 fans to AT&T Stadium outside Dallas.

And if anything, football is even bigger in West Texas. Out here, a “nearby” road game is generally considered one that’s merely two hours away — maybe in Midland or Wichita Falls or Weatherford — as opposed to one in Amarillo (four hours northwest) or El Paso (6½ hours west). On late Friday afternoons in the fall, those highways are jammed with folks making their way somewhere for a football game.

“It’s just different here,” said Anthony Williams, Abilene’s first Black mayor, who served from 2017 until deciding last fall not to run for reelection. “Football is embedded in who we are.”

Williams played for Abilene High, one of the three large high schools in town, along with Cooper and Wylie. He was mayor when the town approved roughly $10 million in funding to build indoor practice facilities at Abilene and Cooper, which opened this summer. (Wylie, which sits in a wealthier area at the south end of town and has its own school district, already had an indoor facility.) Before, the schools would have to cancel practice when temperatures rose above a certain threshold — which they frequently did.

Williams, 55, has a special reverence for the subset of women known as football moms. After his father was murdered when Williams was 4, his mother, Jacqueline, made it her mission to bond with him over football. “Every Sunday, just me and her,” Williams recalled. “We’d eat real good and watch football. So it was more than just entertainment.”

For a Black kid from the poor side of town who started playing tackle at age 10 and went on to play at Abilene High, football represented something important.

“When I put my helmet on and lined up against the other side, my Zip code didn’t matter. And neither did my mother’s income,” he said. “It was you and me. And some of the variables our society places value on, and that give some people advantages — none of that mattered.”

Still, like many people in Abilene, Williams wonders if football’s primacy here is a thing of the past. “It’s different than it was,” he said.

At a community level, football is every bit the engrossing, unifying force it has always been, with the singular power to bring a sizable percentage of a town’s populace together on Friday nights. But at an individual level, and at a family level, longtime observers of Abilene’s football scene can sense something slipping away.

“You look at a community like this, and yeah, on a Friday night, high school football — it’s every bit as big a deal for the community,” said Tim Howk of Tuscola, Tex., 20 minutes south of Abilene, who coaches his son’s seven-on-seven touch football team there. “But I think there are fewer kids who see that high school football experience to be as big a deal as it was maybe 20 years ago when I was in high school.”

Much of it has to do with population growth (or lack thereof) and shifting demographics. While the overall population of Texas exploded — by 16 percent — between the 2010 and 2020 U.S. Censuses, in Abilene it grew only incrementally, rising just 7 percent, to about 125,000 residents. Flat or declining enrollments at Abilene High and Cooper High led to their football programs being downgraded from the highest classification of Texas high school football, Class 6A, to the next level down, 5A, within the past decade. Only Wylie High, in the prosperous south end of town, has seen significant growth, moving up from Class 4A to 5A in 2018.

And while the statewide high school football numbers have slipped, not all sports in Texas have seen similar declines. Participation in boys’ soccer, adjusted for enrollment, has grown 35 percent since 2010, The Post’s analysis found.

“In some areas of the state, you can see where soccer has gotten really, really big,” said Aaron Roan, the head football coach and athletic coordinator at Cooper. “A lot of folks have moved in from other countries, and a lot of them play soccer. … But I can tell you, from a community perspective, it hasn’t changed. Here at Cooper High School, football is a driving force for the campus. Because it brings together so many groups: It brings your band, your Cougarettes, your ROTC, your administration, your student body.

“All of them have a common theme on Friday nights. They’re all going to get together and cheer on the Cougars.”

ABILENE’S HIGH SCHOOL PROGRAMS have managed to maintain a high level of performance even in the face of changing priorities and shifting demographics: Abilene (11-3), Cooper (5-7) and Wylie (8-4) all made the playoffs this season, and all three won at least one playoff game. But when you look one level deeper, at the youth football level, it appears trouble could be on the way.

Williams, the ex-mayor, likes to say his most useful on-the-job training for that position came as the head of the West Texas Youth Football Association, which he fell into after coaching his sons with the Abilene Bucs youth team. At its peak, the WTYFA had nine teams — eight in Abilene and a ninth in Sweetwater, 45 minutes west — and by Williams’s estimation, some 1,700 kids, including cheerleaders, pulling in families from every socioeconomic and racial demographic in town.

Now, the WTYFA is no more, having disbanded in 2019. There are only three remaining youth football teams in Abilene — the Abilene Bucs, Abilene Cowboys and Wylie Bulldogs — with total participation of around 400 kids. They play in regional leagues that require travel to the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex, the Midland-Odessa area and other far-flung locales for games. The cost involved for all that transit creates a self-perpetuating system that keeps participation down.

There are any number of reasons for the WTYFA’s demise, including internal politics and accusations over forged birth certificates and ineligible players, but one central factor keeps coming up: the onset of football’s CTE crisis, and especially Hollywood’s depiction of it in the 2015 Will Smith movie, “Concussion.”

“The numbers went down after that movie came out,” said LaMour Boykins, who has coached for the Bucs for 22 years. “People started to realize what all can happen [in football]. Parents started doing their research and saying, ‘You know, that’s a lot of hitting for these young kids.’ ”

Boykins said his own son, Isaiah, who was playing for Abilene High at the time, came to him after seeing the movie and said, “Uh, Dad, I don’t think I want to play anymore.” And what happened then? “He continued to play,” Boykins said. “But he got three concussions in a year and a half, and he just called it quits. He was like, ‘I’m done. I’ve got a life ahead of me.’ ”

As a lifelong football man, Boykins said, his son’s decision to quit “kind of hurt.” “But as a dad, you want him to be healthy,” he said. “His head is more important than scoring touchdowns.”

Jay Williams, president of the Abilene Cowboys youth football organization, agreed the movie was the turning point, adding that the flood of families that left in its wake cut across racial and socioeconomic lines. “It was just across the board,” he said. “That first year or two, the numbers plummeted.” Like others involved in Abilene’s football scene, he worries that the decline of local youth football will eventually manifest itself at the high school level. And Williams, like many here, blame the media’s continued portrayal of football as dangerous, even as the game works to transform itself.

“We don’t hit like we used to hit,” Jay Williams (no relation to the ex-mayor) said. “The way we used to hit 20 years ago compared to now? It’s 180 degrees. No comparison. Games are still games. But in practice, we don’t hit. We do tackling drills, but we use dummies.”

On a recent Saturday morning at Abilene’s Curly Hayes Field, moms and dads watched from metal bleachers or camper chairs as kids as young as 6 — from the Bucs and Bulldogs — slammed into each other on the field below. “Hit somebody, D!” a young mom screamed from the stands. With the youngest kids, coaches stand behind the line of scrimmage directing traffic. Still, any incomplete pass was likely to prompt four or five kids to pounce instinctively on the dead ball.

Beyond the sidelines, the Bucs’ moms, as football moms have been doing for decades, watched with a combination of excitement, pride and anxiety, the precise recipe differing from person to person. Everyone acknowledged the risks, but opinions differed as to how seriously to take it.

“I believe in the coaches, 100 percent, to teach them [the right way to tackle] and prevent that type of stuff,” said Ashley Gonzalez, who has five boys, ages 5 through 16, who have played, are playing or will play for the Bucs. “I know they can get concussions. But conflicted? No. To me, it happens. It’s part of the sport.”

Kendall Barajas, the mother of two Bucs players, ages 9 and 11, said she has conveyed to them her golden rule: “If they were to get a concussion, they’d be done,” she said. “Because we’re not messing around with [their brains]. I’ve had friends whose kids have had three, four concussions. I’m not going to be that person. That’s their brain. They’re still developing.”

Their numbers may be smaller now, but something keeps bringing these football families back, year after year, for another go-round, Mitey Mites (first- and second-graders) becoming Junior Pee Wees (third and fourth) and finally full-fledged Pee Wees (fifth and sixth). Some families, like the Gonzalezes, can spend two decades ushering one son after another through the program.

What keeps them coming back, even in the face of the inherent danger, is the thing that remains constant amid all the noise and upheaval: Football still matters.

“As a mom, I wouldn’t trade any of it,” said Amber Peck, who sent her two boys through the Bulldogs youth program, then on to Wylie High. “My sons grew immensely as people, as players, as leaders. It’s about helping these young boys become productive young men who will give back to society when they’re older, regardless of whether they want to go on to be Division I athletes. This sport does that.

“You could probably say every sport does that. But it’s a smaller scale. … We’ve done other sports, too. But a Little League Baseball team is 11 boys. A football team is 40 boys. It’s a whole different scale of working together. It’s different. Football is different.”

IF YOUTH FOOTBALL IN ABILENE has dwindled from some 1,700 kids to around 400, what happened to the rest? There may be a dozen or more answers, but one stands out: A significant number of kids and families who might otherwise be playing tackle have instead signed up with seven-on-seven touch leagues or flag football programs.

The biggest seven-on-seven program in Abilene, run by the Big Country Fellowship of Christian Athletes, has nearly tripled in size since 2020, from around 125 to around 325 this year, according to area representative Jamey Calvery. While Calvery acknowledged the program has drawn mostly White families, outreach into minority communities has succeeded in changing that dynamic.

“Around here, seven-on-seven is rising now, more than it ever has before,” Calvery said. “And it’s due to concussions.”

Among the kids who played in the FCA’s seven-on-seven program this fall was the fifth-grade son of Aaron Roan, Cooper High’s head coach. The boy won’t play tackle until seventh grade — the same way Roan himself, also the son of a high school coach, was brought up.

“This is just my personal belief: As a coach, I don’t see a great advantage to starting early in pads. There’s a lot of development of the body that’s still occurring,” Roan said “… That’s also a vulnerable age. For me, personally, I don’t want to burn my kids out before they get an opportunity to play at the high school level.”

In Texas, something endorsed by high school football coaches is, by definition, a mainstream position. And starting one’s kids in a non-tackle form of football, and keeping them out of pads until seventh grade, has become mainstream.

Former Wylie quarterback Case Keenum, arguably the most prominent NFL player Abilene has ever produced, didn’t start playing for the Bulldogs’ youth tackle program until seventh grade.

From appearances, Clark and Jordan Harrell would be prime candidates for starting their son early in tackle football. Both of their fathers are legendary high school football coaches in Texas, and Clark Harrell, currently an assistant coach at Wylie High, played quarterback at Abilene Christian in the late 2000s; his older brother, Graham, set national passing records at Texas Tech and finished fourth in the Heisman Trophy voting in 2008.

But none of the Harrell boys played tackle football before seventh grade, and Clark and Jordan Harrell have decided to do the same with their own 8-year-old son, whom they started in seven-on-seven touch.

“My dad always said there weren’t any benefits to starting earlier. I knew even before I married Clark that was going to be my approach. And when I married into [the Harrell] family, they all said the same thing,” said Jordan Harrell, a writer and interior designer. “I feel like people don’t realize. They feel like they’re giving their kid a leg up by starting them [in tackle] sooner. I just want them to know: You’re not.”

The Harrells have decided to let their son make his own choice about football once he reaches seventh grade, but doing so required a leap of faith that Jordan Harrell has struggled with and is likely to continue struggling with.

“It’s hard being a coach’s wife, because I feel like I see things now as a mom that I never did before I had kids. It’s a lot harder watching games now and seeing the injuries. The tackling feels more violent than it did before kids,” she said. “I love football, and I love watching it. But I feel like I know too much now, so it makes it hard to make a decision as far as my own kid.”

That’s the thing about 7-year-olds and 10-year-olds. They eventually reach seventh grade, the unofficial threshold of football self-governance, leaving moms, and a good number of dads, with some highly complicated feelings to work through. Even in places where football is king.

“There are so many good parts of football, and some of us maybe want to hold onto those good things and block the other things out,” Kari Leong said. “So you have to think, ‘Do the good things outweigh the bad?’ That’s what every mom has to decide for herself, and every family has to decide. What are you prioritizing? In our family we’ve chosen life and health and brainpower.

“But we’re still hoping to be able to be a part of the game. That’s where we are.”

To measure tackle football participation rates, The Post collected data from the National Federation of State High School Associations’ annual reports. The NFHS doesn’t require state associations – which include public and, depending on the state, some private schools – to follow a specific process for collecting this data, and states have varying approaches to account for schools that do not submit their roster sizes. In the Post’s analysis, only boys who participated in 11-player football are included.

In general, years refer to the fall of an academic year, so football participation in the 2022-23 school year is described as 2022. Most participation rates are adjusted based on public high school enrollment, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. The values for 2022 are projections. When The Post analyzed trends that began before 2010, numbers were adjusted based on the U.S. population, according to intercensal estimates from the U.S. Census.

Data reporter Emily Giambalvo contributed to this report. Editing by Joe Tone. Copy editing by Ryan Romano. Photo editing by Toni L. Sandys. Design by Andrew Braford. Design editing by Virginia Singarayar. Projects editing by KC Schaper.

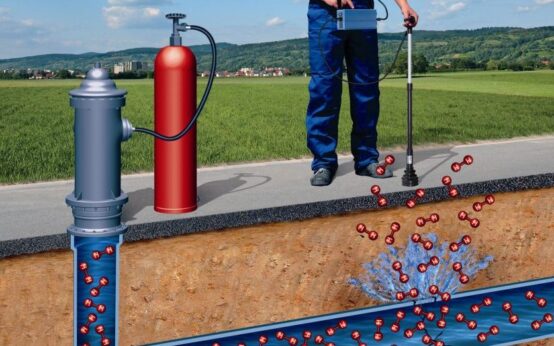

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024  Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven

Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven  Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez

Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez  Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today

Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today