College football’s offseason comes when its season is still decidedly on, with players’ newfound — and justified — free agency occurring while practices are ongoing and bowl games fill the TV lineup. The sport’s leaders — that term is, of course, used loosely — have chosen chaos over order. The result is confusion.

Lane Kiffin, you coach Mississippi, and you have spent the week trying to get your team ready to face Penn State in the Peach Bowl. Take it away.

“It’s a terrible system,” Kiffin told reporters in Atlanta leading up to Saturday’s game. “ … I wouldn’t think any other sports, professional sports, have ever set up a system where free agency starts while the season is still going.

“So it really makes no sense. You can leave. You can stay. You can go other places. Coaches can call you — and our season is still going. It would be like before the NFC or AFC playoffs start in a couple weeks, all of a sudden, ‘Hey, free agency, the week before, opens!’ ’’

There’s a lot going on here and not much that makes sense. Let’s be clear from the jump: College athletes should have the right to transfer without penalty — the old sit-out-a-year-rule was garbage — just like any other college student can transfer without consequences. The athletes produce the product. The athletes should have rights. The athletes aren’t the problem.

What has resulted, though, are several red-letter days on the college football calendar that are completely out of order. It’s as if the sport’s alphabet starts E-B-A-C-D.

First comes the opening of the transfer window — this year, Dec. 4. That’s two days after the conclusion of the conference championship games and one day after the CFP selection committee makes its choices.

Players can transfer through Jan. 2 — which happens to be the day after the CFP semis. Oh, and in the middle of it comes early signing day Dec. 20. All incoming freshmen have to warily watch the players in the transfer portal, while those potential transfers cast a suspicious eye right back. Even if coaches aren’t making official depth charts, players and their parents are. It’s a puzzle figuring out where a kid might have the best opportunity to play, except the pieces never stop moving.

So consider Murphy’s predicament: If Ewers got hurt against Washington, he might be thrust into action — meaningful action — on the sport’s biggest stage. But if he’s thinking about his career — and he is, understandably — he knows Ewers may return to Texas for what would be his third season in 2024. He also knows former No. 1 recruit Arch Manning — yes, of those Mannings — replaced Ewers in a late-season blowout win over Texas Tech while Murphy watched from the sideline.

Murphy wants real playing time as a college quarterback. His options this month: Stick around through the playoffs and maybe watch the Longhorns win a national title — and even help them do it. Or he could leave, either now or later. There’s another transfer window in April, by which point Murphy still might be behind Ewers and Manning. Wait and transfer then, and he would have lost a semester of workouts with a new school.

So last week, Murphy announced he would transfer to Duke — and the Longhorns’ practices and preparations for the program’s biggest game since it played for the national title following the 2009 season are changed because of it.

The problem here isn’t that there’s an early signing period. The problem is that it coincides with a period in which there has been unprecedented player movement, a trend that doesn’t figure to stop. Can’t they somehow be separated?

This system was created in 2017 so players could graduate early from high school and enroll in college in January — thus giving them an offseason in a high-level strength program as well as an extra spring practice session. But that was before players were allowed to transfer without sitting out a season, which means it was before the transfer portal was jammed like rush hour on a Los Angeles freeway.

So the NCAA works thusly: One rule is put in place because it makes sense at that moment, but when another rule is adopted to address a separate issue, it’s done piecemeal. There is no one stepping back and holistically asking, “Does the big picture make sense?”

Oh, and another thing: Because transfers have become so central to most programs, it’s possible — even probable — the teams that reached the playoff following the 2023 season will be compromised in 2024. Michigan, for instance, will either have J.J. McCarthy back for his senior season as the Wolverines’ quarterback — or McCarthy will leave for the NFL.

“I’m completely in the present moment,” McCarthy said last week in not addressing his intentions. With a national title at stake, good for him. But that uncertainty means the bevy of quarterbacks in the transfer portal can’t really consider Michigan. Indeed, according to rankings of transferring players compiled by On3.com, only three of the top 25 transfers nationwide are headed to the four playoff teams. That’s one fewer than will land at Ole Miss, whose coach is benefiting from what he calls “a really bad system.”

One final element: the bowl games. These sideshows long ago transformed from being rewards for a well-played season to holiday programming for the TV networks. To that end, they still work well, because who doesn’t like stumbling into an entertaining game to divert attention from loved ones? (Don’t answer that.)

But what are we even watching? Between outgoing transfers and players opting out of playing to protect their health in preparation for the NFL draft, the depth charts in many bowl games are virtually unrecognizable.

North Carolina played the Duke’s Mayo Bowl without quarterback Drake Maye and leading receiver Tez Walker — and got pummeled by West Virginia, 30-10. Southern California played the Holiday Bowl without 2022 Heisman Trophy winner and presumed No. 1 draft pick Caleb Williams — and redshirt sophomore Miller Moss threw for six touchdowns. Oklahoma played the Alamo Bowl without transferring quarterback Dillon Gabriel. Oregon State and Notre Dame might have provided a good quarterback matchup in the Sun Bowl, but neither the Beavers’ DJ Uiagalelei (transfer) nor the Irish’s Sam Hartman (draft prep) suited up. Texas A&M was down 31 players and using a fourth-string quarterback in its Texas Bowl loss to Oklahoma State.

The list — Ohio State quarterback Kyle McCord, Maryland quarterback Taulia Tagovailoa, etc., etc., ad infinitum — is longer. And it leaves the non-playoff bowl games with a spring game feel. The games can be competitive and compelling, but they don’t really relate to the season just past.

College football has long been chasing the problems that dog it rather than seeing what’s coming and getting out ahead. Next year, throw the expanded, 12-team College Football Playoff into the mix. The dates for four first-round games: Dec. 20-21 — happen to align with this year’s early-signing period.

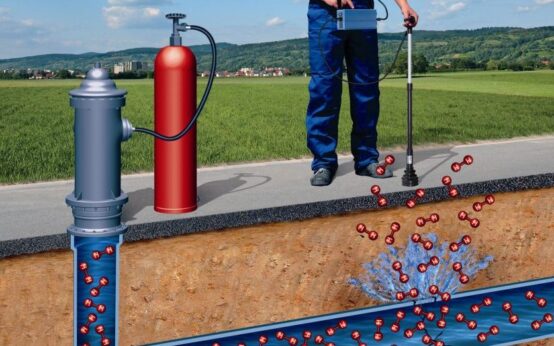

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024  Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven

Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven  Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez

Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez  Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today

Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today