The incongruity is the bowls’ fault, because the major bowl games never really relinquished their unearned control of the sport’s postseason and refused to allow any more than four teams into a bracket when the format debuted in 2014. (If you’re ever in doubt about who’s at fault in college football come January, blame the Rose Bowl.) Florida State’s snub in favor of one-loss Alabama is a byproduct of an ungovernable sport’s greed growing in dangerously lopsided directions.

It’s sort of a shame (although justifiable) that the four-team format will be defined by its omission of a team, because the schools that will play in Monday’s semifinals are steeped in narrative during a season in which the sport itself changed at a pace previously unseen in American sports. All of these programs are stories in their own right, and together they represent the successes and failures of college football’s first playoff era.

There is no reality in which Michigan hoists its first national championship since 1997 absent the asterisk of cheating.

From a pure football standpoint, such a caveat is entirely unfair.

That’s not just my own opinion, it’s the consensus I built from a network of coaches, all with varying degrees of dirty hands from the same types of gray-area gamesmanship. Not only is signal-stealing ubiquitous, it’s efficacy is debatable.

For most of the playoff era, Michigan was a non-factor while programs such as its Rose Bowl opponent Alabama and archrival Ohio State flourished. Of course, Michigan fans chose to blame their also-ran purgatory on the sport’s moral rot rather than the actual culprit: their own alumnus-inbred mismanagement, from Dave Brandon to Warde Manuel to Brady Hoke to even Jim Harbaugh, at least the one who couldn’t beat the Buckeyes. There is no explanation for Michigan’s years of mediocrity beyond its management of players and coaches and resources. The Wolverines lacked in all these areas despite boasting the access, money and prestige necessary to compete with similar brands.

But then Harbaugh became another version of himself, a Michigan Man still with Michigan standards intact and yet competent enough to smack down the sport’s Pharisees: A Harbaugh who could steamroll Ohio State in Columbus, and this season a Harbaugh so efficient he could delegate nearly a month of nonconference games to assistant coaches during his suspension with no noticeable deficiencies.

It’s a minor tragedy we didn’t spend this fall analyzing the refinements and solutions Harbaugh implemented to elevate this program from a Big Ten also-ran into a 38-3, three-time conference champion since 2021.

Nothing revealed to date in the ongoing Connor Stalions sideline videotaping investigation reveals a smoking gun with enough caliber to credulously advantage the Wolverines more than their own talent or scheme. Simply put, Michigan was good enough to win without whatever Stalions obtained, and regardless of who in the organization knew it was happening.

But as unfair as the cheater label might be, Michigan’s earned it. By his own admission, Stalions is a zealot, a man with an actual manifesto, a human being so warped by Michigan’s cultural rhetoric he enrolled in the Naval Academy as a part of a larger plan to one day help … Michigan football.

One day the NCAA might determine Stalions’s actions to be entirely his own, but his ideology — and therefore his motive to conduct a national surveillance campaign — springs directly and ironically from the “It’s hard to beat the cheaters” pablum Harbaugh and Michigan supporters have suffocated the narrative with for decades.

Michigan is an exceptional football team, and it arguably performed as the nation’s best during a regular season fraught with distractions internal and otherwise. But the culture of bunk moral superiority it has long espoused carries a consequence: It’s responsible for why the Wolverines will be forced to share a national title with the ignominy of earning it like any of the other playoff-era champions they denounced: by being another cheater.

The Crimson Tide is inevitable. It is the blueprint. If you love what college football has become, you owe it to Alabama. If you hate it, you can point in the same direction.

With three national titles during the preceding Bowl Championship Series era, Nick Saban’s machine was well in progress before the advent of the playoff, and it rolled right through the playoff era, too: The Tide boasts six national title game appearances, three championships, and nine total playoff wins (including seven by double digits).

For a decade, Alabama has suffocated the idea of another standard, be it by outlasting momentary surges from programs such as LSU or a competing dynasty such as Clemson, which is now scrambling to maintain a portion of the longevity Alabama has enjoyed. Another national title from the Tide would also bookend and rebuke the back-to-back mini-dynasty former Alabama coordinator Kirby Smart built at Georgia, arguably the greatest current threat to its reign.

Scores of teams have attempted to replicate this program, and a few have even beaten it when it mattered most. But none has broken Alabama.

A litany of books have already attempted to pinpoint the how of the Saban era’s unbridled success. The shortest explanation is that Saban is a machine that kills uncertainty: Before he took the reins of a distressed historic power in 2007, college football was defined by a variance that seemed intractable: The players are students, so talent comes and goes. So, too, will the help, because good assistant coaches will always be poached to become head coaches elsewhere. Boosters have outsized influence and will inevitably meddle. All in all, there is a season to success, and fortunes wane.

Saban stamped that idea out. And as it produced previously unseen title-caliber consistency, his ruthless micromanagement became a dogma and ultimately a religion.

Right before the playoff era, in 2013, Texas tried to lure Saban out of Tuscaloosa with a then-staggering $100 million contract.

Saban’s decision to stand pat became the defining moment of modern college football, and the standard for the playoff era was set.

Another Alabama championship would seem to prove that standard is the only one capable of delivering in perpetuity.

If money solved all problems, Texas would be a utopia. So, too, would its flagship university, defined in the playoff era by the lack of success its seemingly infinite advantages could not prevent.

In January of 2019, I spoke to a then-Texas assistant weeks after the Longhorns beat Georgia in the Sugar Bowl to cap their first 10-win season since 2009. Assuming all was positive in Austin and the program was finally shaking off its torpor of inefficiency, I was shocked to hear his assessment of the offseason:

“It’s impossible to stop the noise around these kids. It’s impossible to keep a team culture here with so much on the outside convincing them they’re great for no reason.”

No football program, at least no football program of privileged means, was more associated during the playoff era with unearned entitlement and physical “softness” than Texas.

The former is that classic saw of “too many cooks” in the gilded UT booster class. The latter is hard to qualify, but it was a common refrain among opposing coaches: Under a few very different head coaches, Texas did the same thing: recruited five-star talent you could hit in the mouth once and never worry about again.

The unfortunate truth about football is that it’s a violent occupation that requires more than our society’s acceptable standards of commitment or tenacity. Long cursed by their own “We’re Texas” culture, the Longhorns finished 5-7 in Coach Steve Sarkisian’s 2021 debut, then 8-5 last season and are now 12-1 entering the Sugar Bowl against Washington. What’s different from previous upswings in Texas history is the manner in which the Longhorns ascended: Even a casual fan can’t help but notice Texas’s ferocity. A program universally considered pillow-soft by rivals now seeks out contact, wins ugly games in ugly ways and operates with physicality as a standard and finesse an afterthought.

If it seems suspiciously like the Alabama program it beat in September, that’s the design, although the architect is still unlikely. Yes, Sarkisian is a former Alabama assistant and possibly the greatest example yet of Saban’s signature ability to hire failed head coaches and rehabilitate them. Sarkisian imploded at USC in 2015 and worked his way back up, but of the Saban tree graduates, no one expected an otherwise mild-mannered “West Coast guy” to be the one to finally seal off the echo chamber in Austin and deliver a product worthy of the available resources.

Washington: What won’t be

The Huskies are the most of-the-moment program in the national title picture: As their conference implodes, a transfer quarterback and a seemingly fearless offensive scheme from coordinator Ryan Grubb are the highlights of Coach Kalen DeBoer’s lightning-fast renovation after the Huskies’ ill-fated succession plan between longtime coach Chris Pedersen and initial replacement Jimmy Lake.

If you’re looking for objectively fun football, Washington is arguably the most entertaining team in the sport. Too bad the Huskies showed up two years too late to maybe keep the Pac-12 respectable, and in turn keep college football a healthy, thriving sport in every time zone.

As it stands, the last Pac-12 season in existence could end with the one thing the league so desperately needed to justify its mismanaged modern identity in the playoff years — a national title-winning program.

Football results weren’t what doomed the Pac-12, and the idea one great season from one great team would’ve changed a historically bungled outfit is foolish. Still, it’s hard to watch a season in which Oregon and Washington dominated the playoff conversation months after they fled to the Big Ten (effective next season).

None of this is Washington’s problem now. The Huskies haven’t been this exciting since 1991, so who cares if the neighborhood’s burning? Washington didn’t hire former Pac-12 commissioner Larry Scott to run the league into the ground, nor were they obligated to go down with Scott successor George Kliavkoff’s ship.

If anything, Washington’s presence in the playoff is something of a miracle considering the obstacles placed in front of Pac-12 programs first by the league itself and then by a cabal of TV executives fattening inventory. Seattle isn’t close to Alabama or Texas or Atlanta or any of the markets that historically dominate in TV ratings or produce future recruits. The league’s stupidly conceived, entirely self-managed network was virtually shut out of carriers, meaning the Huskies and their ilk struggled to market their games nationwide while partnerships such as the Big Ten and Fox and the SEC and ESPN created the current billionaire’s stranglehold of the “Big Two.”

And yet the Huskies reached the game’s biggest stage by hiring a great coach and wooing an electric quarterback in Michael Penix Jr., and also by slyly sneaking out the back door of the crumbling Pac-12 for the certainty of the Big Ten.

Whether it matters in any on-field way that they’re not playing Oregon State and Cal in favor of Purdue and Michigan State will be difficult to gauge, at least for a while. Whether the dissection of the Pacific time zone by television executives puppeteering conference realignment damages West Coast football in a measurable way is hard to predict. How it helps college football or college sports in any way other than TV revenue is impossible to figure.

But those aren’t Washington’s problems. Hoisting a national championship is a great salve for survivor’s guilt, and it should help with the flights to Indiana and New Jersey, too.

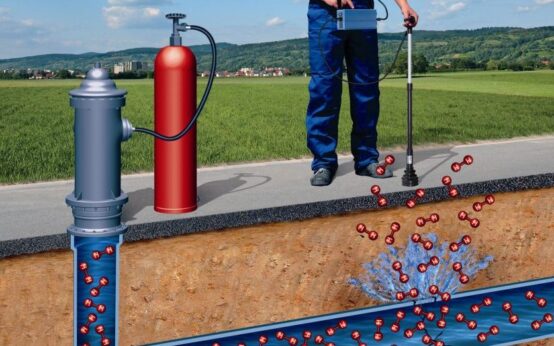

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024  Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven

Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven  Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez

Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez  Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today

Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today