There’s an inherent problem in asking athletes to speak their truths but then rejecting those truths once they’re revealed. If not everyone in society loves baseball, it makes sense that there would be a small percentage of baseball players who don’t love baseball. It’s only logical.

Admitting that, though, is dicey. Especially for Rendon, especially given his contract, especially given his contributions — or utter lack thereof — in the four seasons since signing that seven-year, $245 million deal designed to help push Mike Trout and Co. to postseason success. He exited his seven-year stint with the Washington Nationals as a World Series hero who was among the best third basemen in the game, worth 18.6 wins above replacement in his last three D.C. seasons alone, according to FanGraphs.

In four seasons with the Angels, he has a total WAR of 3.6. He has been mostly underproductive or absent, a horrendous combination.

Now this. Is baseball even a priority, he was asked?

“Oh, it’s a priority for sure,” Rendon said. “Because it’s my job. I’m here, aren’t I?”

There’s a tone-deafness here that’s undeniable. But it’s also clear that the sports-watching public would prefer its athletes love the sports the way it does, not to mention appreciate the life-changing money they earn doing it. There is cognitive dissonance in watching someone get paid to play a game, then shrug off any joy gleaned from playing it. Rendon simply doesn’t care about the reaction to his attitude, so he’ll live with the fallout.

But it’s also true that what Rendon does — play third base for the Angels — is a job. It might be a game, but putting in what’s necessary to be good at it unquestionably qualifies as work. The best athletes are lauded as “professionals” for the way they “go about their business.” Their jobs play out as competitions that we watch from the stands and on TV, pure entertainment. But to master a sport, athletes must treat it as their vocation, not their avocation.

If Rendon was producing in Anaheim as he did in Washington, his nonchalance toward his job — and by extension his team — could probably be dismissed. Given what he has been reduced to — the past three seasons in which he hit .235, slugged .364, had an OPS of .701 and appeared in just 148 games — there’s a temptation to draw a line connecting his comments Monday, which could be interpreted as a lack of commitment, and his inability to get on the field in the first place and produce when he does.

What a fall. It’s hard to overstate how good Rendon was when at his best. From 2017 to 2019, only four players in baseball posted a higher OPS than Rendon’s .953. In his final two seasons in Washington, “Tony Two Bags” led the National League in doubles. In his walk year of 2019, no one in the game drove in more runs. In Game 6 of the 2019 World Series, he drove in the Nats’ first run, then broke the game open with a two-run bomb in the seventh. In the decisive Game 7, his blast in the seventh broke the seal off Houston starter Zack Greinke and set up the heroics of Howie Kendrick later in the inning.

It’s all indelible. It also seems so long ago, as if those feats were performed not just by a different player but a different person.

“I love baseball,” Rendon told my colleague Dave Sheinin in 2018, an interview that offered rare insight into what makes Rendon tick. “I love being on the field. I love competing. But I’m not a fan of everything that comes with it. No offense — I’m not a fan of the interviews. I’m not a fan of people coming in the clubhouse. I’m not a fan of everyone treating you different because you play a sport. How am I different than anyone else? I’m a human being, and I have my faults, too.”

That’s a different, more publicly palatable way of trying to get across his sentiments from this week.

In my mind, Rendon has always been unnecessarily difficult. During his time in Washington, after the games in which he knew he had to speak with reporters because he was either the hero or the goat, he developed a practice of putting a chair in front of him, ensuring people had to keep a distance, small but telling. One year, upon arriving at spring training and enduring a perfunctory session with reporters, he ended the chat with, “Okay, talk to you guys on April 2” or whatever was the date of Opening Day. It’s all silly stuff that didn’t much matter, but he was difficult to cover. He also contributed in very meaningful ways — commitments of both time and money — to the Nationals Youth Baseball Academy.

In his remarks this week — remarks that followed a season in which he didn’t play after July 4 because of a sometimes-mysterious leg injury — Rendon said he was cleaning out old emails and found one that he had sent to himself back in 2014, one in which he openly laid out the pros and cons of staying in baseball. That old saying that if you find a job you love, you’ll never work a day in your life? Apparently, Rendon never found one.

A decade later, he was asked, how might that pro-and-con list look?

“It’s a lot different,” he said. “I’m married. I have four kids.” [Side note: He has produced a lot more at home than he has for the Angels.] “My priorities have changed since I was in my early 20s. So, definitely, my perspective on baseball has been more skewed.”

Baseball is an absolute meat grinder even for those who love it. For those who don’t — even if they’re insanely talented — it has to be some version of worse. No one has to make Anthony Rendon love the game and the ancillary tasks that go along with it.

It would be nice, though, if he could reorganize his thoughts and articulate an appreciation for what the game has provided him — and for his top priority, his family. Baseball has enveloped him with a $245 million hug. It’s not a terribly big ask to get a tiny squeeze back.

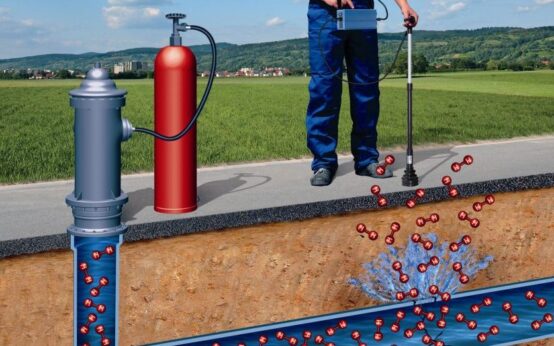

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024  Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven

Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven  Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez

Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez  Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today

Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today