The first female Supreme Court justice, and the only one in the Cowgirl Hall of Fame, lay in repose in Washington on Monday, and as her casket was carried into the dim columned Great Hall between the lines of former clerks to be surrounded by frozen marbled men and their umber portraits, you couldn’t help but think, wait, they’re taking her in the wrong direction, she was a creature of sun and sky. Just then the swirling wind whipped up, and the half-masted flags switched direction for just a moment, to the southwest. That was where her unique combination of strong hands and high mindedness originated.

O’Connor was accustomed to being severely underestimated and she continues to be, judging by the sparse line who paid respects Monday morning. It’s said her legacy — written in opinions on reproductive freedom, and affirmative action — has been undone by the court’s more recent decisions. This couldn’t be more wrong, and it misapprehends her real importance, which was to totally rewrite what was publicly achievable as a woman in a man’s profession. She believed in the power of the “qualitative individual” even in the face of enormous institutions, and from her appointment in 1981 until her retirement in 2006, whether on the high court or the tennis court where she had a slugging forehand, she demonstrated that accomplishment could trump sexism. As she once told a doubles partner, “If you don’t keep score, someone else will. I learned that on the Court.”

Across 160,000 acres of stony canyons on the Arizona-New Mexico border, O’Connor learned something else, a softness of movement in unforgiving environments, how to listen closely to the winds and rustles in the grasses, and distinguish “whatever it is can scratch you, bite you or puncture you,” as she wrote in a memoir she co-authored with her brother Alan, “Lazy B: Growing Up on a Cattle Ranch in the American Southwest.”

This deference to her surroundings, and attunement of eye and ear, would serve her well on the court, the alpha-manliness of which was illustrated by Byron “Whizzer” White’s crushing handshake. Deference, of course, does not mean weakness. It merely means respect, and in her it cloaked a deeply embedded strength, as one of her colleagues in the Arizona state legislature learned to his embarrassment. The story is in the excellent biography of O’Connor, “First,” by Evan Thomas. A legislator who chaired appropriations was such a notorious drunk that O’Connor confronted him. He railed at her, “If you were a man, I’d punch you in the nose.” She shot back, “If you were a man, you could.”

When she was born, her parents brought her home to a four-room adobe ranch house with no electricity or plumbing, lit by coal lamps, and with a privy 75 yards outside, circumstances she would live in until she was 7, when her father installed some improvements. The cowboys who worked the ranch slept on the screen porch. “My baby-sitters were tobacco chewing, unshaven, unbathed, Levi-clad, and tough as nails,” she wrote. She grew up to the creaking of windmills pumping trickles of water from catch basins and dirt tanks, eating mostly beef and beans. “It was no country for sissies,” she observed.

She learned to handle a rifle before she was 10 and to drive a truck as soon as she could see over the dashboard. Her first pet was a bobcat, and she tried to domesticate a coyote and failed. By the eighth grade she could work a roundup with the cowboys for long hours in the dust. She rode horses named things like Scarhead, Hell Bitch, and Hemorrhoid, the latter because you felt so bruised after riding him. Her father treated sore muscles with cow manure poultices. The sensibility it created was hardened but fine, and without an ounce of false sentiment.

“I felt the horse’s every move,” she wrote in her memoir. “I was aware of his breath, his sweat. When he stopped to pee the strong smell of urine enveloped us, and drops of liquid splattered my boots. When he expelled gas, I heard and felt it. I often talked to my horse while riding.”

The only thing she liked better than cowgirling was reading, and with a capaciousness for learning she skipped two grades in high school and galloped through Stanford’s undergraduate program and law school in just six years. At the time, only 2 percent of all law students were women, and no one would hire her. She worked for no pay at the San Mateo County district attorney’s office. And slowly, there emerged into the legal world this woman so perfectly suited to perform under the great pressure of being the first on that bench full of black robes.

She undoubtedly felt the weight of it, the danger of being seen as not competent, and she dealt with it as adroitly as she moved her 1,200-pound horse at the noise of a rattlesnake. She did not lack for competitiveness. According to Thomas, during her confirmation process she was introduced to the head pro at Burning Tree, the all-male golf club in the Maryland suburbs frequented by presidents. She said to him, smiling yet pointed, “I can’t wait to play your course.”

She established an aerobics class for women in the high court’s gym, which had previously been dominated by all-male pickup basketball games in which White threw flagrant fouls. It sent a message that women were athletes too. But it made another statement as well, about the freedom to define womanhood. “She never acted as though she needed to be a man to be there,” remarked one of her former clerks in a tribute by the Penn law school.

She chafed at the Chevy Chase Club’s policy that women couldn’t tee off on Saturdays until 11 a.m. She dealt with it by arriving at 10:30 a.m. each weekend and sitting right by the first tee, greeting every man who teed off ahead of her. Shamed, they changed the rule.

Her biography is chock-full of anecdotes illustrating how fully and fearlessly she lived in her body and in nature. She broke her shoulder skiing. She went to a NASCAR race for a speaking engagement, got in one of the cars and said, “Step on it!” On a fishing trip in Alaska, she had to mace a grizzly bear. The only thing that seems to have truly frightened her physically was breast cancer, and even then, she covered her deep anxiety by telling her secretary, “What an annoyance.”

Time after time what came through in O’Connor’s legal opinions, almost like secret-ink handwriting, was that hardy yet empathetic intelligence of the outdoorswoman, who could do the work of a man yet hear the wing of a spar hawk. Strength dueled with delicacy in her most controversial case, Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), in which she upheld reproductive rights without “undue burden” of state interference. Conservatives hated the decision for its careful movement through the intellectual thicket — Justice Antonin Scalia called it “a jurisprudence of confusion.” But complexity did not mean confusion, any more than deference did weakness. “The destiny of the woman must be shaped to a large extent on her own conception of her spiritual imperatives and her place in society,” the opinion stated. Nothing could have been clearer.

O’Connor shaped her own destiny. At the head of her casket was her Supreme Court portrait. It is lighter and airier than most, and it shows that weather-scored face, eyes rich with moral intelligence. Her hair is as white as Washington’s wig. She looks like a Founding Mother.

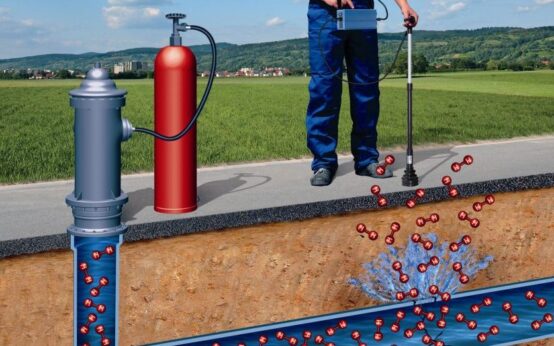

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024  Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven

Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven  Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez

Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez  Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today

Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today