Being different did not stop record attendance this year, a blockbuster broadcast deal and the arrival of Lionel Messi. The 29-team circuit is doing just fine.

And amid all the quirks, the league does observe most soccer conventions. Since its birth in 1996, MLS has participated in a 110-year-old national tournament, the U.S. Open Cup, that has involved amateurs headquartered at a discount liquor store and first-tier sides owned by billionaires.

But in a late-day news dump Friday, MLS announced it will skip the tournament next year. Like a child throwing a sandbox tantrum, MLS is taking its toys and going home. Commissioner Don Garber has grumbled about the Open Cup for years, but no one expected him to lead a full-scale exodus.

The league has not completely cut ties: It will send developmental squads from MLS Next Pro, its self-created third division. The Seattle Sounders, for instance, will be represented by the Tacoma Defiance — a fitting team name under the circumstances.

Such action is the equivalent of the Premier League clubs en masse ditching the FA Cup and entering their under-21 squads.

Venting on social media, some MLS fans fumed about the league thumbing its nose at tradition, while those who support smaller clubs seethed about losing the chance to beat the big boys in a single-game, knockout competition.

So why did MLS withdraw? In Friday’s news release, the league said the Open Cup would “provide emerging professional players with additional opportunities for meaningful competition.” Many MLS teams call up young players for the competition, the league reasoned, so why not use a squad full of them?

The other reason cited by the league rang truer: “The move also benefits the MLS regular season by reducing schedule congestion, freeing up to six midweek match dates.”

In other words, the calendar is full and something had to go.

But MLS created the congestion by launching a massive new tournament that no one asked for. The Leagues Cup involves all 47 MLS and Mexican Liga MX clubs and consumes four summer weeks.

MLS has long been obsessed with tapping into the Mexican American market, and the Leagues Cup is the latest vehicle in that vein. The tournament also provided more live content for MLS’s broadcast partner, Apple TV Plus, which is paying up to $2.5 billion over 10 years; MLS doesn’t own Open Cup broadcast rights.

Aside from the Leagues Cup, MLS’s docket includes the 34-game regular season, the playoffs and the All-Star Game. Early next year, 10 MLS teams will compete in the Concacaf Champions Cup (formerly called the Concacaf Champions League), the annual regional championship modeled after the famed European competition.

MLS schedule-makers also must take into account large-scale international events held in the United States, such as the 2024 Copa América, the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup, probably the 2025 Concacaf Gold Cup and the 2026 World Cup.

It’s a lot, so MLS unloaded the Open Cup. It hasn’t ruled out returning. “MLS remains committed to working with [the U.S. Soccer Federation] to evolve and elevate the Open Cup for everyone involved in the years ahead,” the league said.

To be fair, the Open Cup is a flawed tournament. Conceptually, it seems like a winner. Practically, it has sputtered in the shadows.

Some MLS teams move early-round home games to smaller, alternative venues because, until the late stages, ticket demand is low. Managing a busy schedule and a tight roster, coaches often hold out regulars in favor of reserves and prospects.

Some non-MLS venues are substandard. The financial rewards are small. TV coverage is limited, and a confusing number of online platforms show matches. The tournament just means much more to the lower divisions than to MLS.

In May, Garber criticized the Open Cup and its organizer, U.S. Soccer, the sport’s domestic governing body.

“From our perspective,” Garber said during a USSF board of directors meeting, “it is a very poor reflection on what it is we’re trying to do with soccer at the highest level.”

Despite its flaws, the Open Cup offers something MLS doesn’t: consequences and charm. Without fear of relegation and with a low threshold for making the playoffs, the MLS regular season is monotonous.

The Open Cup is more like the NCAA basketball tournament — if the NCAA were to invite teams from all three of its divisions, plus NAIA schools.

A lower-division club packs a humble park and hosts a muscular visitor. A journeyman who dreams of an MLS contract scores a once-in-a-lifetime goal from great distance. A goalkeeper who plays soccer as a side hustle makes the clinching save in a shootout.

These are the moments that help make soccer so appealing in much of the world. It’s Grimsby Town, from England’s fourth flight, pulling off five upsets against higher-tier opponents, including Southampton of the Premier League, to reach the FA Cup quarterfinals this past spring.

It’s third-division Union Omaha advancing to the Open Cup quarterfinals in 2022 and second-tier Sacramento Republic playing for the title the same year.

It’s D.C. United winning the 2013 crown amid a 3-24-7 regular season. That was the most recent of United’s three Open Cup titles, which rank fourth among MLS teams. Because United is the only U.S.-based organization yet to launch a MLS Next Pro team — it has plans to do so in Baltimore — D.C. will have no presence in the 2024 tournament.

Since 1996, only one non-MLS team has lifted the trophy. The Rochester Rhinos, now defunct, sprung from the second division in 1999. But that misses the point. The journey and the storylines make the Open Cup special — and make soccer like no other.

MLS, though, has put its own self-interests ahead of the game at large. For that, Garber and the league deserve a red card.

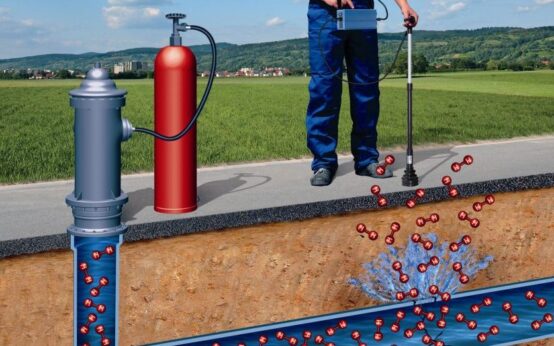

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024  Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven

Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven  Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez

Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez  Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today

Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today