Okay, depending on where you work — or really, where your client plays — there are some rules. Most states, though not all, technically require you to register as an agent. But for the most part, that just means filling out a short form and sending a check, whether it’s $100 in New York, $200 in North Carolina or $1,500 in South Carolina. In Louisiana, you don’t have to pay a fee if you are licensed to practice law in the state. In Hawaii, the fee is $357 if you apply between July 1 of an odd-numbered year and June 30 of an even-numbered year, then $497 if you apply between July 1 of an even-numbered year and June 30 of an odd-numbered year.

And a test? There are no required tests to show a baseline of knowledge about NIL contracts, the transfer portal or anything else the modern college athlete faces. It’s not all that different from getting ordained online to officiate your friend’s wedding.

And wide-ranging enforcement? Basically, there is none. Good luck!

“I have seen so many people call themselves NCAA-certified even though the NCAA doesn’t certify NIL agents,” said Darren Heitner, a Florida-based sports and entertainment lawyer who specializes in NIL. “Everyone likes to say that NIL transactions and athletes finally getting their due is the wild, wild west. Well if you want to talk about the wild west, it’s the agent piece that’s ground zero for that, because so many of them are ignoring the actual laws. And in the past few years, I haven’t heard one story about a state’s attorney general or secretary of state coming down on an NIL agent for not being properly registered.”

So, something has to give, right? Horror stories about “agents” — trying to make a quick buck in the transfer portal, or sign a contract that scores an exorbitant share of an athlete’s future earnings — are way too common. One former NIL director at a major school recalled an agent asking for 50 percent of the money a player would make from the donor-funded collective that supported the athletic department. A collective leader at an ACC school said he recently saw social media messages between a freshman football player and a sales rep for a major cable service provider, the rep promising the player a lucrative deal if he leaped into the transfer portal with him. Shockingly, the cable rep had no searchable experience in sports.

When the NCAA started allowing athletes to profit off their name, image and likeness on July 1, 2021, tens of thousands of college students became potential clients for sports agents or “sports agents” overnight. It didn’t matter that no one knew how the market would work. What mattered was that a market existed at all.

In the 2½ years since, a patchwork of quickly-enacted state laws has created a complicated landscape. And what many can agree on is the need for more regulation — or any regulation — of NIL agents, especially considering how much money is being pumped into revenue sports by those collectives.

While schools and collectives can try to screen who represents their athletes, most states don’t require NIL agents to disclose their relationships or contracts with clients. Unlike in major professional leagues, there’s also no players association to standardize the requirements to be an agent, nor is there a collective bargaining agreement because college athletes are not considered employees (yet). The NCAA does have a certification process for agents looking to represent athletes ahead of the NBA draft. As for NIL, specifically, the NCAA has pitched a voluntary registration system for agents, allowing athletes to view them in a centralized place and rate their experience for others to see. This is a small sliver of a larger proposal for student-athlete NIL protection that will be voted on in January.

“I mean, the qualifications for being an NIL agent are the same as being a quote-unquote NFL draft expert,” said Neil Stratton, founder of Inside the League, which offers services to NFL scouts, agents and players preparing for the draft. “You declare yourself one.”

That’s not to say every NIL agent is a rogue actor. Far from it, actually. Major agencies such as CAA, WME and Excel, among others, now have NIL wings. Many people with backgrounds in marketing or branding have registered through the proper channels and educated themselves on the space. Or take Jack Adler, a recent Syracuse graduate, who started as an NIL agent while in school, then grew his company, Out2Win Sports, into a legitimate sports marketing firm with a long list of clients.

But that still leads to another question: What might more regulation even look like?

Among its many functions, Stratton’s company helps aspiring NFL agents prep for a tough entry exam. It costs $2,500 for two cracks at the test. Stratton estimated a 20 to 30 percent chance of passing the first time, then around 50 percent the second. Along the way, there’s an extensive background check. If a person passes, it costs $2,500 more to officially register. Then they have three years to sign a player on a 90-man roster — the bloated size after the draft each spring — or their license is revoked.

Tom Livolsi, founder of Savage Wolves, a collective supporting North Carolina State athletics, has started an NIL compliance company that plans to have a certified agent program that universities would have to buy into. Other ideas include an official agent database (similar to the NCAA’s idea) and forcing agents to disclose when they are not registered with an “athletic association” such as the NCAA or a conference (something Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Tex.) proposed in his October draft for a federal bill to standardize NIL rights). But again, determining who would enforce these measures, and how they would enforce them, remains a puzzle.

“At the very least, there should be a test that forces people to study up on contracts and NCAA regulations before becoming an NIL agent,” said Adler, who has continued building Out2Win after graduating this past spring. “It wouldn’t fix everything, but it couldn’t hurt.”

Which leads to a final question (though there certainly are more): Is a democratized agent landscape all bad?

Adler is an NIL success story, showing how the market can benefit athletes and enterprising students who might want to work in sports after graduating. To land the first NIL deal for a Syracuse football captain in 2021, Adler put on a suit and walked from one business to the next, eventually landing a partnership with a local gym. He was 20 years old. He had a law student look over any contracts before his athletes signed. And when Out2Win grew beyond New York, Adler had the agents he hired register in each state in which they represented athletes.

He sees NIL as a way for students to carve out their own internships during the school year. And his path, starting with squinting at contracts in his dorm room, hasn’t clouded his view of what should happen next. He wants you to be an NIL agent if that’s your dream, same as it was his. He just sees a pressing need for some sort of process to becoming one. He wishes you luck, too.

“It’s great that anyone, at any age, can work in this industry,” Adler said. “But for the safety of the athletes and NIL long term, putting in actual work has to be a big part of that.”

Albert Samaha contributed to this report.

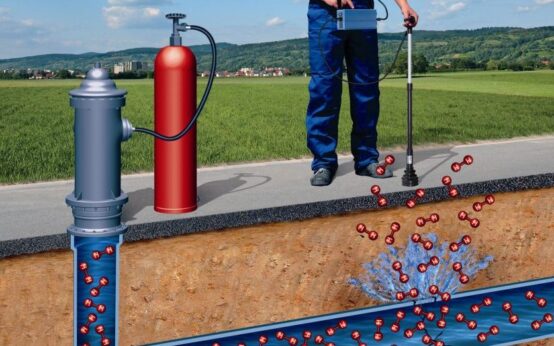

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024  Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven

Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven  Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez

Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez  Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today

Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today