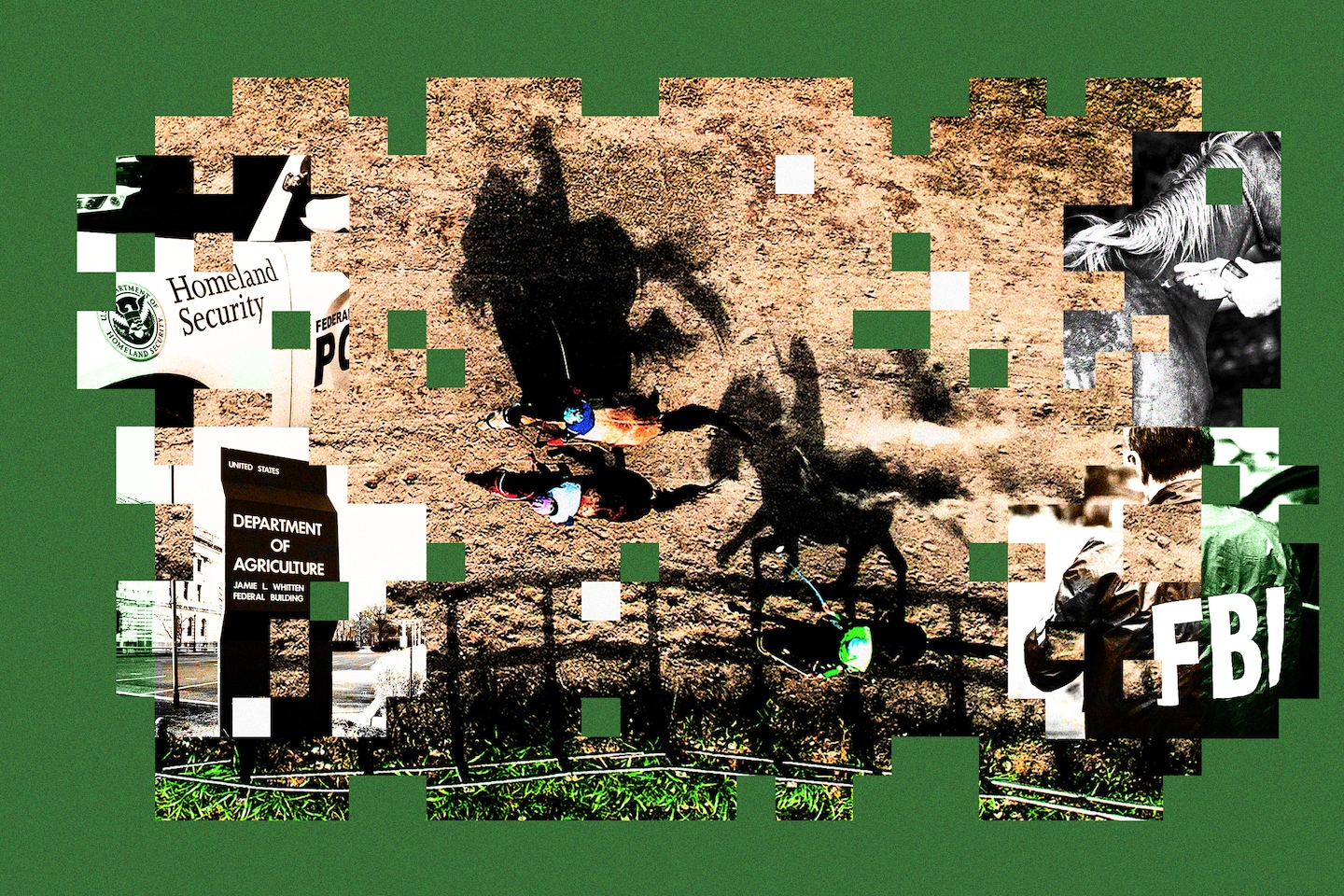

And just like that, the government would have delivered a shot across the bow of so-called “bush tracks,” a booming, lawless industry with documented ties to international organized crime.

But the cavalry never arrived.

The big race day came and went with no raid. The USDA agents leading the investigation said they had been outranked by more powerful federal partners who scuttled their plans, interviews and records show.

“Basically, FBI shut us down and took over the case,” senior USDA investigator Kenneth Cash said. “They’re a three-letter agency and we’re a four-letter agency. We get treated like four-letter words.”

The track continued to operate undisturbed.

Eventually, in August 2022, the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) raised concerns about the track to journalists. The Washington Post observed horses being injected with syringes, including one found to contain methamphetamine, and jockeys utilizing shock devices. Finally, last June, local authorities arrested seven people connected with the track.

But the charges were relatively minor. Six jockeys, all of whom have also raced on regulated tracks, were charged with cruelty to animals after PETA provided evidence of them repeatedly whipping and using a shock device on horses. An alleged bookie was charged with illegal commercial gambling, a felony. All seven defendants have pleaded not guilty.

Federal agents abandoned plans to raid the track even as a separate case showed, according to prosecutors, that a once-central figure to Rancho El Centenario was allegedly involved in the sale of large amounts of methamphetamine and other drugs. Meanwhile, the disbarred attorney who owns the horse track, Arthur “Brutz” English IV, has not been charged and continues to run a full race schedule. He recently taunted local authorities by distributing souvenir pens shaped to look like syringes.

“We handed them the evidence on a silver platter, and they really promised they would take action,” PETA senior vice president Kathy Guillermo said of federal authorities. Local authorities, PETA said, were able to secure charges despite the federal government, which destroyed evidence including drug-laden syringes provided by the group’s investigators.

The story of the abandoned federal investigation, which has not been previously reported, is based on court records, text messages, emails, notes and interviews with federal and local law enforcement officials and animal rights activists. It sheds light on the disjointed response to a lawless cottage industry blamed for animal cruelty, brazen horse doping, the spread of equine illness and its alleged proximity to drug trafficking, money laundering and other crimes. The industry, meanwhile, is thriving: By the federal government’s official tally, the number of known bush tracks has more than doubled, to 192, in the last year and a half.

Spokespeople for both the FBI and the USDA said they could not confirm or deny the existence of an investigation.

Lamar County (Ga.) Sheriff Brad White said his ability to investigate the horse track was stymied by federal agencies repeatedly backing out of joint investigations.

“We had actually worked with three different federal agencies trying to get an investigation,” White said, adding that his homogenous police force didn’t have officers who could go undercover at the track, where the patrons are mostly Latino men. “I need Hispanics and I need money, and I still don’t have either one.”

White said that while he had made the arrests he could using PETA video evidence, it was far from the crackdown on Rancho El Centenario that he feels is warranted. “Still to this day, I believe it needs to be delved into further,” White said.

Jonathan Adams, district attorney for Lamar and two other counties, said there was little more they could do without federal assistance or a change in Georgia law to make unregulated racing a crime.

“My hands are tied,” Adams said. “I implore our legislators to make these bush tracks illegal or at the very least mandate their regulation.”

English was defiant in a recent interview, saying he expected the jockeys accused of using whips or a shocking device to be exonerated.

“I don’t approve of them using an electronic shocking device,” English said. “But on the other hand, many people use electronic shocking devices to train dogs, including the local sheriff’s office here.”

English acknowledged distributing the novelty syringe pens.

“Just thumbing my nose at ya,” English said. “There’s nobody out here drugging animals.”

A jockey’s fall spurs interest

PETA’s investigators first learned of Rancho El Centenario in March 2021, when they received an email tip about the track. A jockey, Roman Chapa, had suffered a fatal accident there. The emailer complained of horses breaking down and being shot on the track.

PETA sprung to action, sending undercover investigators to Georgia. Over multiple trips, they recorded jockeys and trainers appearing to whip and shock horses to make them run faster, as well as a trackside bookie collecting cash bets. They recorded footage of a horseman injecting a horse in the neck and then discarding a syringe, which the investigators picked up. When PETA sent it to an equine lab at the University of California, Davis, the results showed it contained cocaine. Other spent syringes the investigators found on the ground also contained cocaine and methamphetamine, a lab report shows.

PETA called the DEA that fall, according to notes and emails provided by the animal-rights group, and learned that the track was already notorious to multiple federal agencies — and was currently under investigation by the FBI and USDA.

That’s when the activists were connected with two USDA special agents, Cash and Dustin McPhillips, who shared their zeal for cracking down on animal abusers with potential links to deeper criminality. The USDA’s investigative arm, within its Office of the Inspector General, has a fraction of the manpower and clout of behemoth agencies such as the DEA, FBI and HSI. But they didn’t lack for confidence. McPhillips, a former Air Force veteran and CIA employee, described his unit of the USDA as “Special Ops” for the agriculture department, according to PETA’s notes.

The agents acknowledged the logistical hurdles: They explained that there were “different alphabets involved” in the operation, the notes show, and that figuring out where to store seized horses would be a challenge. But the USDA investigators appeared even more headstrong than PETA.

“They didn’t seem to want to discuss a less ambitious goal,” a PETA investigator wrote to her colleagues after meeting with them. “Cash said that they want to prosecute all the people and rescue all the animals. … Maybe they’re being naive, but if enough government agencies want action on this facility, maybe they can make this happen.”

Cash confirmed that they planned a multiagency raid on the track but said he could not discuss details. McPhillips declined to comment when reached by The Post.

During a meeting at PETA’s Norfolk headquarters, the nonprofit’s investigators gave the agents evidence bags containing syringes, memory cards and a thumb drive. The notes show that McPhillips appeared to be aiming to raid a busy race day before the end of the year, such as the track’s annual championship races in October.

Races at Rancho El Centenario can attract thousands of spectators and are patrolled by armed guards. According to a PETA investigator’s email, McPhillips told her that some of the other agencies are calling this a “high-risk operation. … [B]ut as someone who has helicoptered into danger and worked in Afghanistan, he doesn’t consider it that high risk.”

After another meeting with McPhillips’ supervisors and a prosecutor, PETA’s top attorney said he was told the raid was a matter of when, not if.

“They would not provide any details at all,” PETA Chief Legal Officer Jeff Kerr wrote to his colleagues, “other than to say that it is a priority, they are actively working the case and are going to take action.”

McPhillips was soon at full throttle, emailing PETA detailed questions about specific cuadras — the stables managing particular horses — and making plans to test blood samples. The raid would “deter this kind of activity from happening ‘for years’ if possible,’ ” according to a PETA email at the time.

Then, in 2022, something shifted. McPhillips’s communication with PETA grew sporadic and noncommittal. He was engrossed in a cockfighting operation, he said.

PETA, growing impatient, threatened to take their evidence public.

“Horses are dying on the track of catastrophic injuries, being drugged with illegal, controlled substances, shocked with electrical devices, and beaten,” a PETA investigator emailed McPhillips. “For the safety and welfare of the horses, we do not want to delay much longer.”

Finally, the USDA delivered the news: The plans for a raid were over. In a phone call afterward, according to a PETA investigator’s email, an emotional McPhillips said that after he tried to get a warrant, he encountered delays and was finally told to stand down. He lamented that some federal agencies “play better in the sandbox than others,” the PETA investigator wrote.

In an interview, Cash expressed frustration that the FBI shelved an ambitious operation for an investigation with a more limited scope. “We had a much bigger picture there than what the FBI was looking at,” Cash said.

The FBI was involved in the arrest of one figure closely associated with Rancho El Centenario. English, the ranch’s owner, credited Jose Guadalupe Favela, a “farmhand,” for sharing with him years ago the idea of turning his family pecan farm into a bush track. But Favela, the feds allege, has long been part of a crew of drug traffickers who move kilos of methamphetamine and other drugs out of ranches in Georgia. Favela and three others were indicted last year; his attorney did not respond to a request for comment.

English said Favela hasn’t been involved in Rancho El Centenario in years, after English fired him. “I got information that he was involved in the drug trade, and I didn’t want that business affiliated with mine,” English said.

The Lamar County sheriff’s office is 11 miles down winding country roads from Rancho El Centenario. Sheriff White is in a complicated position: Several of his officers have worked second jobs as off-duty security guards for the track, using county cruisers.

White told The Post that was his way of keeping an eye on the track. “My people can’t be undercover,” he said. “Everybody knows everybody.”

Following the collapse of the federal investigation, White said, McPhillips began pressuring local authorities to take action before PETA embarrassed them by going public.

“He had told me that if we didn’t make an arrest or do a search warrant or something with what he had done, that PETA was going to release all that stuff,” White said. “And I said, ‘Listen, we want to make a solid case that will go through the court system.’”

But there is little indication that White was in the midst of such a case by August 2022, when The Post published a story detailing chaos at the Georgia track. PETA simultaneously sent a letter to White and Adams, the district attorney. Deputies and prosecutors then opened a case, meeting with PETA investigators and lawyers in Georgia to collect their evidence and statements.

Last summer, six jockeys were charged with misdemeanor cruelty to animals. All were identified in PETA’s letter to the authorities. Zenaida Cardenas-Munoz, who PETA had accused of being the most prominent bookie at the track, was charged with two counts of commercial gambling, a felony.

Attorneys for the jockeys and alleged bookie did not respond to requests for comment.

PETA had argued that English and other operators of the track could be charged under Georgia’s racketeering laws. DA Adams disagreed, noting that in Georgia, there is no regulated horse racing — and thus no statutes making unregulated racing illegal.

“That’s where the real problem is,” Adams said. “If unregulated bush tracks were illegal here, I could charge the property owners.”

“Under the current law, we’re not doing anything wrong,” said English, who added that the reports of horses being injected at his tracks was a misunderstanding of “common agricultural process. … The reality is when veterinarians deal with large animals, they bring syringes and injectables to race sites, to barns, to stables, to ranches.”

Evidence that PETA claims could have legally debunked that explanation was apparently a casualty of the aborted federal investigation. The USDA never returned the syringes that the group collected from the track. That included the syringe PETA investigators recorded a trainer using to inject a horse in the neck — and which a lab found contained cocaine.

Last August, a PETA lawyer seeking the return of the syringes was informed by a USDA official, Assistant Special Agent in Charge Miles Davis, that they were destroyed “consistent with their normal process when a case is closed.”

“He also expressed support for our work,” PETA lawyer Jared Goodman wrote in an email to his colleagues, “and hope that we’d be able to find a way to stop it.”

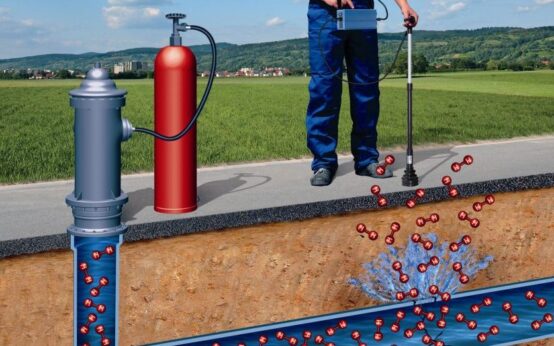

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024

Best Underground Water Leak Detection Equipment 2024  Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven

Best Backyard Ideas: Turn Your Outdoor Area Into a Creative and Calm Haven  Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez

Babar, Rizwan are good players but not whole team, says Mohammad Hafeez  Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today

Pak vs NZ: Green Shirts aim to bounce back against Kiwis today